Pericarditis

| Pericarditis | |

|---|---|

| |

| An ECG showing pericarditis, with ST elevation in multiple leads and slight reciprocal ST depression in aVR. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | Sharp chest pain, better sitting up and worse with lying down, fever[1] |

| Complications | Cardiac tamponade, myocarditis, constrictive pericarditis[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Typically sudden[1] |

| Duration | Few days to weeks[3] |

| Causes | Viral infection, tuberculosis, uremic pericarditis, following a heart attack, cancer, autoimmune disorders, chest trauma[4][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, electrocardiogram, fluid around the heart[6] |

| Differential diagnosis | Heart attack[1] |

| Treatment | NSAIDs, colchicine, corticosteroids[6] |

| Prognosis | Usually good[6][7] |

| Frequency | 3 per 10,000 per year[2] |

Pericarditis (PER-i-kar-DYE-tis) is inflammation of the pericardium, the fibrous sac surrounding the heart.[8] Symptoms typically include sudden onset of sharp chest pain, which may also be felt in the shoulders, neck, or back.[1] The pain is typically less severe when sitting up and more severe when lying down or breathing deeply.[1] Other symptoms of pericarditis can include fever, weakness, palpitations, and shortness of breath.[1] The onset of symptoms can occasionally be gradual rather than sudden.[8]

The cause of pericarditis often remains unknown but is believed to be most often due to a viral infection.[4][8] Other causes include bacterial infections such as tuberculosis, uremic pericarditis, heart attack, cancer, autoimmune disorders, and chest trauma.[4][5] Diagnosis is based on the presence of chest pain, a pericardial rub, specific electrocardiogram (ECG) changes, and fluid around the heart.[6] A heart attack may produce similar symptoms to pericarditis.[1]

Treatment in most cases is with NSAIDs and possibly the anti-inflammatory medication colchicine.[6] Steroids may be used if these are not appropriate.[6] Symptoms usually improve in a few days to weeks but can occasionally last months.[3] Complications can include cardiac tamponade, myocarditis, and constrictive pericarditis.[1][2] Pericarditis is an uncommon cause of chest pain.[9] About 3 per 10,000 people are affected per year.[2] Those most commonly affected are males between the ages of 20 and 50.[10] Up to 30% of those affected have more than one episode.[10]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Substernal or left precordial pleuritic chest pain with radiation to the trapezius ridge (the bottom portion of scapula on the back) is the characteristic pain of pericarditis. The pain is usually relieved by sitting up or bending forward, and worsened by lying down (both recumbent and supine positions) or by inspiration (taking a breath in).[11] The pain may resemble that of angina but differs in that pericarditis pain changes with body position, where heart attack pain is generally constant and pressure-like. Other symptoms of pericarditis may include dry cough, fever, fatigue, and anxiety.[citation needed]

Due to its similarity to the pain of myocardial infarction (heart attack), pericarditis can be misdiagnosed as a heart attack. Acute myocardial infarction can also cause pericarditis, but the presenting symptoms often differ enough to warrant diagnosis. The following table organizes the clinical presentation of pericarditis differential to myocardial infarction:[11]

| Characteristic | Pericarditis | Myocardial infarction |

|---|---|---|

| Pain description | Sharp, pleuritic, retro-sternal (under the sternum) or left precordial (left chest) pain | Crushing, pressure-like, heavy pain. Described as "elephant on the chest." |

| Radiation | Pain radiates to the trapezius ridge (to the lowest portion of the scapula on the back) or no radiation. | Pain radiates to the jaw or left arm, or does not radiate. |

| Exertion | Does not change the pain | Can increase the pain |

| Position | Pain is worse in the supine position or upon inspiration (breathing in) | Not positional |

| Onset/duration | Sudden pain, that lasts for hours or sometimes days before a person comes to the ER | Sudden or chronically worsening pain that can come and go in paroxysms or it can last for hours before the person decides to come to the ER |

Physical examinations

[edit]The classic sign of pericarditis is a friction rub heard with a stethoscope on the cardiovascular examination, usually on the lower left sternal border.[11] Other physical signs include a person in distress, positional chest pain, diaphoresis (excessive sweating); possibility of heart failure in form of pericardial tamponade causing pulsus paradoxus, and the Beck's triad of low blood pressure (due to decreased cardiac output), distant (muffled) heart sounds, and distension of the jugular vein (JVD). The presence of a triphasic pericardial friction rub on auscultation. A bedside electrocardiogram (ECG) shows widespread concave ST elevation and PR depression throughout most of the limb and precordial leads.

Complications

[edit]Pericarditis can progress to pericardial effusion and eventually cardiac tamponade. This can be seen in people who are experiencing the classic signs of pericarditis but then show signs of relief, and progress to show signs of cardiac tamponade which include decreased alertness and lethargy, pulsus paradoxus (decrease of at least 10 mmHg of the systolic blood pressure upon inspiration), low blood pressure (due to decreased cardiac index), (jugular vein distention from right sided heart failure and fluid overload), distant heart sounds on auscultation, and equilibration of all the diastolic blood pressures on cardiac catheterization due to the constriction of the pericardium by the fluid.[citation needed]

In such cases of cardiac tamponade, EKG or Holter monitor will then depict electrical alternans indicating wobbling of the heart in the fluid filled pericardium, and the capillary refill might decrease, as well as severe vascular collapse and altered mental status due to hypoperfusion of body organs by a heart that can not pump out blood effectively.[citation needed]

The diagnosis of tamponade can be confirmed with trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE), which should show a large pericardial effusion and diastolic collapse of the right ventricle and right atrium. Chest X-ray usually shows an enlarged cardiac silhouette ("water bottle" appearance) and clear lungs. Pulmonary congestion is typically not seen because equalization of diastolic pressures constrains the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure to the intra-pericardial pressure (and all other diastolic pressures).[citation needed]

Causes

[edit]

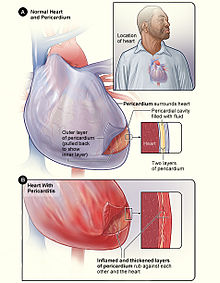

Figure B shows the heart with pericarditis. The inset image is an enlarged cross-section that shows the inflamed and thickened layers of the pericardium.[12]

Infectious

[edit]Pericarditis may be caused by viral, bacterial, or fungal infection.

In the developing world the bacterial disease tuberculosis is a common cause, whereas in the developed world viruses are believed to be the cause of about 85% of cases.[6] Viral causes include coxsackievirus, herpesvirus, mumps virus, and HIV among others.[4] Also observed by James Blachly, Strep Throat can also cause pericarditis due to the heart sac filling up.

Pneumococcus or tuberculous pericarditis are the most common bacterial forms. Anaerobic bacteria can also be a rare cause.[13] Fungal pericarditis is usually due to histoplasmosis, or in immunocompromised hosts Aspergillus, Candida, and Coccidioides.[citation needed] The most common cause of pericarditis worldwide is infectious pericarditis with tuberculosis.[citation needed]

Other

[edit]- Idiopathic: No identifiable cause found after routine testing.[4]

- Autoimmune disease: systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatic fever,[4] IgG4-related disease[14][15]

- Myocardial infarction

- Dressler's syndrome[4]

- Peri-Myocardial Infarction Pericarditis[16]

- Trauma to the heart[4]

- Uremia (uremic pericarditis)[4]

- Cancer[4]

- Side effect of some medications, e.g. isoniazid, cyclosporine, hydralazine, warfarin, and heparin

- Radiation induced[4]

- Aortic dissection[4]

- Postpericardiotomy syndrome—such as after CABG surgery[4]

- Vaccines-such as smallpox[17][18] and COVID-19 Vaccines[19] in rare yet documented instances.

Diagnosis

[edit]

The preferred initial diagnostic testing is the ECG, which may demonstrate a 12-lead electrocardiogram with diffuse, non-specific, concave ("saddle-shaped"), ST-segment elevations in all leads except aVR and V1[11] and PR-segment depression possible in any lead except aVR;[11] sinus tachycardia, and low-voltage QRS complexes can also be seen if there is subsymptomatic levels of pericardial effusion. The PR depression is often seen early in the process as the thin atria are affected more easily than the ventricles by the inflammatory process of the pericardium.[citation needed]

Since the mid-19th century, retrospective diagnosis of pericarditis has been made upon the finding of adhesions of the pericardium.[20]

When pericarditis is diagnosed clinically, the underlying cause is often never known; it may be discovered in only 16–22 percent of people with acute pericarditis.[citation needed]

Imaging

[edit]-

Ultrasounds showing a pericardial effusion in someone with pericarditis

-

A pericardial effusion as seen on CXR in someone with pericarditis

On MRI T2-weighted spin-echo images, inflamed pericardium will show high signal intensity. Late gadolinium contrast will show uptake of contrast by the inflamed pericardium. Normal pericardium will not show any contrast enhancement.[21]

Laboratory test

[edit]Laboratory values can show increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN), or increased blood creatinine in cases of uremic pericarditis. Generally, however, laboratory values are normal, but if there is a concurrent myocardial infarction (heart attack) or great stress to the heart, laboratory values may show increased cardiac markers like Troponin (I, T), CK-MB, Myoglobin, and LDH1 (lactase dehydrogenase isotype 1).[citation needed]

Classification

[edit]Pericarditis can be classified according to the composition of the fluid that accumulates around the heart.[22]

Types of pericarditis include the following:[citation needed]

Acute vs. chronic

[edit]Depending on the time of presentation and duration, pericarditis is divided into "acute" and "chronic" forms. Acute pericarditis is more common than chronic pericarditis, and can occur as a complication of infections, immunologic conditions, or even as a result of a heart attack (myocardial infarction), as Dressler's syndrome. Chronic pericarditis however is less common, a form of which is constrictive pericarditis. The following is the clinical classification of acute vs. chronic:[citation needed]

- Clinically: Acute (<6 weeks), Subacute (6 weeks to 6 months) and Chronic (>6 months)

Treatment

[edit]The treatment in viral or idiopathic pericarditis is with aspirin,[11] or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs such as ibuprofen).[4] Colchicine may be added to the above as it decreases the risk of further episodes of pericarditis.[4][23] The drug that helps treat the condition that has developed is aspirin. In this case, the patient is experiencing post-myocardial infarction pericarditis (PIP), which is characterized by chest pain, low-grade fever, and specific findings on physical examination and electrocardiogram. Aspirin is the drug of choice for PIP and is usually already prescribed for secondary prevention following a myocardial infarction. Aspirin acts as an anti-inflammatory drug and helps alleviate the symptoms of pericarditis

Severe cases may require one or more of the following:[citation needed]

- antibiotics to treat tuberculosis or other bacterial causes

- steroids are used in acute pericarditis but are not favored bPrednisone is effective in treating acute viral or idiopathic pericarditis,

- pericardiocentesis to treat a large pericardial effusion causing tamponade

Recurrent pericarditis resistant to colchicine and anti-inflammatory steroids may benefit from a number of medicines that affect the action of interleukin 1; they cannot be taken in tablet form. These are anakinra, canakinumab and rilonacept.[24][25] Rilonacept has been specifically approved as an orphan drug for use in this situation.[26] Immunosuppressive agents, such as Azathioprine and intravenous immunoglobulins, are a novel therapeutic agent which have been effective in treating and preventing recurrent pericarditis, though research on these therapies is limited.[25][27][28][29]

Surgical removal of the pericardium, pericardiectomy, may be used in severe cases and where the pericarditis is causing constriction, impairing cardiac function. It is less effective if the pericarditis is a consequence of trauma, in elderly patients, and if the procedure is done incompletely. It carries a risk of death between 5 and 10%.[25]

Epidemiology

[edit]About 30% of people with viral pericarditis or pericarditis of an unknown cause have one or several recurrent episodes.[6]

See also

[edit]- Acute pericarditis

- Constrictive pericarditis

- Dressler syndrome

- Myopericarditis

- Pericardial effusion

- Purulent pericarditis

- Tuberculous pericarditis

- Uremic pericarditis

- Viral cardiomyopathy

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Pericarditis?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. September 26, 2012. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d Imazio M, Gaita F (July 2015). "Diagnosis and treatment of pericarditis". Heart. 101 (14): 1159–68. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306362. PMID 25855795. S2CID 35310104.

- ^ a b "How Is Pericarditis Treated?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. September 26, 2012. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Tingle LE, Molina D, Calvert CW (November 2007). "Acute pericarditis". American Family Physician. 76 (10): 1509–14. PMID 18052017.

- ^ a b "What Causes Pericarditis?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. September 26, 2012. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M (October 2015). "Evaluation and Treatment of Pericarditis: A Systematic Review". JAMA. 314 (14): 1498–506. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12763. hdl:2318/1576078. PMID 26461998.

- ^ Cunha BA (2010). Antibiotic Essentials. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4496-1870-4.

- ^ a b c "What Is Pericarditis?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. September 26, 2012. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016.

- ^ McConaghy JR, Oza RS (February 2013). "Outpatient diagnosis of acute chest pain in adults". American Family Physician. 87 (3): 177–82. PMID 23418761.

- ^ a b "Who Is at Risk for Pericarditis?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. September 26, 2012. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f American College of Physicians (ACP) (2009). "Pericardial disease". Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program (MKSAP-15): Cardiovascular Medicine. American College of Physicians. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-934465-28-8. Archived from the original on 2010-08-02.

- ^ "Pericarditis". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute .nih.gov. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ Brook I (April 2009). "Pericarditis caused by anaerobic bacteria". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 33 (4): 297–300. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.06.033. PMID 18789852.

- ^ Ibe T, Nakamura T, Taniguchi Y, Momomura S (June 2016). "IgG4-related effusive constrictive pericarditis". European Heart Journal: Cardiovascular Imaging. 17 (6): 707. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jew056. PMID 27044912.

- ^ Atallah PC, Kassier A, Powers S (September 2014). "IgG4-related disease with effusive-constrictive pericarditis, tamponade, and hepatopathy: a novel triad". International Journal of Cardiology. 176 (2): 516–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.046. PMID 25062559.

- ^ Gharacholou S Michael; Vaca-Cartagena F Bryan; Parikh P Pragnesh; Pollak M Peter; Bruce J Charles. "Peri-Myocardial Infarction Pericarditis: Current Concepts". Edelweiss Publications Inc. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Kuntz, J.; Crane, B.; Weinmann, S.; Naleway, A. L.; Vaccine Safety Datalink Investigator Team (2018). "Myocarditis and pericarditis are rare following live viral vaccinations in adults". Vaccine. 36 (12): 1524–1527. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.030. PMC 6437672. PMID 29456017.

- ^ "Myocarditis, Pericarditis, and Dilated Cardiomyopathy after Smallpox Vaccination among Civilians in the United States, January–October 2003". 15 March 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Myocarditis and Pericarditis After mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination". Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Flint A (1862). "Lectures on the diagnosis of diseases of the heart: Lecture VIII". American Medical Times: Being a Weekly Series of the New York Journal of Medicine. 5 (July to December): 309–311.

- ^ Ismail TF (January 2020). "Acute pericarditis: Update on diagnosis and management". Clinical Medicine. 20 (1): 48–51. doi:10.7861/clinmed.cme.20.1.4. PMC 6964178. PMID 31941732.

- ^ Klatt EC. "Cardiovascular Pathology Index Images". The Internet Pathology Laboratory for Medical Education. Florida State University College of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2007-05-24.

- ^ Alabed S, Cabello JB, Irving GJ, Qintar M, Burls A (August 2014). "Colchicine for pericarditis" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (8): CD010652. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010652.pub2. PMC 10645160. PMID 25164988.

- ^ Tombetti, Enrico; Mulè, Alice; Tamanini, Silvia; Matteucci, Luca; Negro, Enrica; Brucato, Antonio; Carnovale, Carla (August 2020). "Novel Pharmacotherapies for Recurrent Pericarditis: Current Options in 2020". Current Cardiology Reports. 22 (8): 59. doi:10.1007/s11886-020-01308-y. PMC 7303578. PMID 32562029.

- ^ a b c Andreis, Alessandro; Imazio, Massimo; Casula, Matteo; Avondo, Stefano; Brucato, Antonio (28 February 2021). "Recurrent pericarditis: an update on diagnosis and management". Internal and Emergency Medicine. 16 (3): 551–558. doi:10.1007/s11739-021-02639-6. PMC 7914388. PMID 33641044.

- ^ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (18 March 2021). "FDA Approves First Treatment for Disease That Causes Recurrent Inflammation in Sac Surrounding Heart". FDA. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Marcolongo, Renzo; Russo, Rosario; Laveder, Francesco; Noventa, Franco; Agostini, Carlo (November 1995). "Immunosuppressive therapy prevents recurrent pericarditis". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 26 (5): 1276–1279. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(95)00302-9. PMID 7594043. S2CID 8236269.

- ^ del Fresno, M. Rosa; Peralta, Julio E.; Granados, Miguel Ángel; Enríquez, Eugenia; Domínguez-Pinilla, Nerea; de Inocencio, Jaime (2014-11-01). "Intravenous Immunoglobulin Therapy for Refractory Recurrent Pericarditis". Pediatrics. 134 (5): e1441 – e1446. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3900. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 25287461. S2CID 12121925.

- ^ Andreis, Alessandro; Imazio, Massimo; Casula, Matteo; Avondo, Stefano; Brucato, Antonio (April 2021). "Recurrent pericarditis: an update on diagnosis and management". Internal and Emergency Medicine. 16 (3): 551–558. doi:10.1007/s11739-021-02639-6. ISSN 1828-0447. PMC 7914388. PMID 33641044.