History of the United States (1849–1865)

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

The history of the United States from 1849 to 1865 was dominated by the tensions that led to the American Civil War between North and South, and the bloody fighting in 1861–1865 that produced Northern victory in the war and ended slavery. At the same time industrialization and the transportation revolution changed the economics of the Northern United States and the Western United States. Heavy immigration from Western Europe shifted the center of population further to the North.

Industrialization went forward in the Northeast, from Pennsylvania to New England. A rail network and a telegraph network linked the nation economically, opening up new markets. Immigration brought millions of European workers and farmers to the Northern United States. In the Southern United States, planters shifted operations (and slaves) from the poor soils of the Southeastern United States to the rich cotton lands of the Southwestern United States.

Issues of slavery in the new territories acquired in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) were temporarily resolved by the Compromise of 1850. One provision, the Fugitive Slave Law, sparked intense controversy, as revealed in the enormous interest in the plight of the escaped slave in Uncle Tom's Cabin, an 1852 anti-slavery novel and play.

In 1854, the Kansas–Nebraska Act reversed long-standing compromises by providing that each new state of the Union would decide its posture on slavery (popular sovereignty). The newly formed Republican Party stood against the expansion of slavery and won control of most Northern states (with enough electoral votes to win the presidency in 1860). The invasion of Kansas by sponsored pro- and anti-slavery factions intent on voting slavery up or down, with resulting bloodshed (Bloody Kansas), angered both North and South. The Supreme Court tried unsuccessfully to resolve the issue of slavery in the territories with a pro-slavery ruling, in Dred Scott v. Sandford, that angered the North.

After the 1860 election of Republican Abraham Lincoln, seven Southern states declared their secession from the United States between late 1860 and 1861, establishing a rebel government, the Confederate States of America on February 9, 1861. The Civil War began when Confederate General Pierre Beauregard opened fire upon Union troops at Fort Sumter in South Carolina. Four more states seceded as Lincoln called for troops to fight an insurrection.

The next four years were the darkest in American history as the nation tore at itself using the latest military technology and highly motivated soldiers. The urban, industrialized Northern states (the Union) eventually defeated the mainly rural, agricultural Southern states (the Confederacy), but between 600,000 and 700,000 American soldiers (on both sides combined) were killed, and much of the infrastructure of the South was devastated. About 8% of all white males aged 13 to 43 died in the war, including 6% in the North and an extraordinary 18% in the South.[1] In the end, slavery was abolished, and the Union was restored, richer and more powerful than ever, while the South was embittered and impoverished.

Economic and cultural changes

[edit]

Developing a market economy

[edit]By the 1840s, the Industrial Revolution was transforming the Northeast, with a dense network of railroads, canals, textile mills, small industrial cities, and growing commercial centers, with hubs in Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia. Although manufacturing interests, especially in Pennsylvania, sought a high tariff, the actual tariff in effect was low, and was reduced several times, with the 1857 tariff the lowest in decades. The Midwest region, based on farming and increasingly on animal production, was growing rapidly, using the railroads and river systems to ship food to slave plantations in the south, industrial cities in the East, and industrial cities in Britain and Europe.[2]

In the south, the cotton plantations were flourishing, thanks to the very high price of cotton on the world market. Cotton production wears out the land, and so the center of gravity was continually moving west. The annexation of Texas in 1845 opened up the last great cotton lands. Meanwhile, other commodities, such as tobacco in Virginia and North Carolina, were in the doldrums. Slavery was dying out in the upper South, and survived because of sales of slaves to the growing cotton plantations in the Southwest. While the Northeast was rapidly urbanizing, and urban centers such as Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Chicago were rapidly growing in the Midwest, the South remained overwhelmingly rural. The great wealth generated by slavery was used to buy new lands, and more slaves. At all times the great majority of Southern whites owned no slaves, and operated farms on a subsistence basis, serving small local markets.[3][4]

A transportation revolution was underway thanks to heavy infusions of capital from London, Paris, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Hundreds of local short haul lines were being consolidated to form a railroad system, that could handle long-distance shipment of farm and industrial products, as well as passengers.[5] In the South, there were few systems, and most railroad lines were short haul project designed to move cotton to the nearest river or ocean port.[6] Meanwhile, steamboats provided a good transportation system on the inland rivers.

With the use of interchangeable parts popularized by Eli Whitney, the factory system began in which workers assembled at one location to produce goods. The early textile factories such as the Lowell mills employed mainly women, but generally factories were a male domain.[7]

By 1860, 16% of Americans lived in cities with 2500 or more people; a third of the nation's income came from manufacturing. Urbanized industry was limited primarily to the Northeast; cotton cloth production was the leading industry, with the manufacture of shoes, woolen clothing, and machinery also expanding. Energy was provided in most cases by water power from the rivers, but steam engines were being introduced to factories as well. By 1860, the railroads had made a transition from use of local wood supplies to coal for their locomotives. Pennsylvania became the center of the coal industry. Many, if not most, of the factory workers and miners were recent immigrants from Europe, or their children. Throughout the North, and in southern cities, entrepreneurs were setting up factories, mines, mills, banks, stores, and other business operations. In the great majority of cases, these were relatively small, locally owned, and locally operated enterprises.[8]

Immigration and labor

[edit]To fill the new factory jobs, immigrants poured into the United States in the first mass wave of immigration in the 1840s and 1850s. Known as the period of old immigration, this time saw 4.2 million immigrants come into the United States raising the overall population to over 20 million people. Historians often describe this as a time of "push-pull" immigration. People who were "pushed" to the United States immigrated because of poor conditions back home that made survival dubious while immigrants who were "pulled" came from stable environments to find greater economic success. One group who was "pushed" to the United States was the Irish, who were attempting to escape the Great Famine in their nation. Settling around the coastal cities of Boston, Massachusetts and New York City, the Irish were not initially welcomed because of their poverty and Roman Catholic beliefs. They lived in crowded, filthy neighborhoods and performed low-paying and physically demanding jobs. The Catholic Church was widely distrusted by many Americans as a symbol of European autocracy. German immigration, on the other hand, was "pulled" to America to avoid a looming financial disaster in their nation. Unlike the Irish, the German immigrants often sold their possessions and arrived in America with money in hand. German immigrants were both Protestant and Catholic, although the latter did not face the discrimination that the Irish did. Many Germans settled in communities in the Midwest rather than on the coast. Major cities such as Cincinnati, Ohio and St. Louis, Missouri developed large German populations. Unlike the Irish, most German immigrants were educated, middle-class people who mainly came to America for political rather than economic reasons. In the big cities such as New York, immigrants often lived in ethnic enclaves called "ghettos" that were often impoverished and crime-ridden. The most infamous of these immigrant neighborhoods was the Five Points in New York City. With increasing labor agitation for higher wages and better working conditions, such as by the Lowell mill girls in Massachusetts, many factory owners began to replace female workers with immigrants who would work cheaper and were less demanding about factory conditions.

Political upheaval

[edit]Wilmot Proviso

[edit]In 1848 the acquisition of new territory from Mexico through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo renewed the sectional debate over slavery. The question of whether the new territory would allow slavery was the main question, with Northern Congressmen hoping to limit slavery and Southern Congressmen hoping to expand the territory in which it was legal. Soon after the Mexican–American War began, Democratic Congressman David Wilmot proposed that territory won from Mexico should be free from the institution of slavery. Called the Wilmot Proviso, the measure failed to pass Congress and thus never became law. This served to unify the majority of Southerners, who saw the Proviso as an attack on their society and their constitutional rights.[9]

Popular sovereignty debate

[edit]With the failure of the Wilmot Proviso, Senator Lewis Cass introduced the idea of popular sovereignty in Congress. In an attempt to hold the Congress together as it continued to divide along sectional rather than party lines, Cass proposed that Congress did not have the power to determine whether territories could allow slavery, since this was not an enumerated power listed in the Constitution. Instead, Cass proposed that the people living in the territories themselves should decide the slavery issue. For the Democrats, the solution was not as clear as it appeared. Northern Democrats called for "squatter sovereignty", in which the people living in the territory could decide the issue when a territorial legislature was convened. Southern Democrats disputed this idea, arguing that the issue of slavery must be decided at the time of adoption of a state constitution, when the request was made to Congress for admission as a state. Cass and other Democratic leaders failed to clarify the issue so that neither section of the country felt slighted as the election approached. After Cass' defeat in 1848, Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas assumed a leading role in the party and became closely associated with popular sovereignty with his proposal of the Kansas–Nebraska Act.[10]

California gold rush

[edit]The election of 1848 produced a new president from the Whig Party, Zachary Taylor. James K. Polk did not seek reelection because he achieved all his objectives in his first term and because his health was declining. From the election emerged the Free Soil Party, a group of anti-slavery Democrats who supported Wilmot's Proviso. The creation of the Free Soil Party foreshadowed the collapse of the Second Party System; the existing parties could not contain the debate over slavery for much longer.[citation needed]

The question of slavery became all the more urgent with the discovery of gold in California in 1848. The next year, there was a massive influx of prospectors and miners looking to strike it rich. Most migrants to California (so-called 'Forty-Niners') abandoned their jobs, homes, and families looking for gold. This huge migration of white settlers to the Pacific coast led to confrontations with Native populations, including the ethnic cleansing of thousands of Native inhabitants. Some historians (and a state governor)[11] have referred to this period lasting into the early 1870s as the California genocide.[12][13]

It also attracted some of the first Chinese Americans to the West Coast of the United States. Most Forty-Niners never found gold but instead settled in the urban center of San Francisco or in the new municipality of Sacramento.[14]

Compromise of 1850

[edit]The influx of population led to California's application for statehood in 1850. This created a renewal of sectional tension because California's admission into the Union threatened to upset the balance of power in Congress. The imminent admission of Oregon, New Mexico, and Utah also threatened to upset the balance. Many Southerners also realized that the climate of those territories did not lend themselves to the extension of slavery (it was not yet foreseen that the Central Valley in California would someday become a center of cotton farming). Debate raged in Congress until a resolution was found in 1850.

President Taylor threatened to personally command an army against any Southern state that would secede from the Union, and he also threatened force against Texas, which laid claim to the eastern half of New Mexico. However, Taylor died of an intestinal ailment in July 1850, and his successor, Vice President Millard Fillmore, was a lawyer by training and far less war-like.

The Compromise of 1850 was proposed by "The Great Compromiser," Henry Clay and was passed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Through the compromise, California was admitted as a free state, Texas was financially compensated for the loss of its Western territories, the slave trade (not slavery) was abolished in the District of Columbia, the Fugitive Slave Law was passed as a concession to the South, and, most importantly, the New Mexico Territory (including modern day Arizona and the Utah Territory) would determine its status (either free or slave) by popular vote. A group of Southern extremists, still not satisfied with the compromise, held two conventions in Nashville, Tennessee calling for secession, one during the summer of 1850 and the other late in the year, but by that point the Compromise had already passed through Congress and been accepted by the Southern states.

The Compromise of 1850 temporarily defused the divisive issue, but the peace was not to last long.[15]

Presidential election of 1852

[edit]Having lost two presidential elections to Whig war heroes, the Democratic Party tried their own by nominating Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire, who had served without great distinction in the Mexican War. Endorsed by Southern Democrats, Pierce openly supported the Compromise and the Fugitive Slave Act. The Whigs rejected the idea of running incumbent President Fillmore, and so instead turned to another war hero in General Winfield Scott. Although a capable man, Scott's haughty personality alienated many voters and Pierce won an easy victory at the ballot box.

Foreign affairs

[edit]The acquisition of the Southwest had made the United States a Pacific power. Diplomatic and commercial ties with China had been first established in 1844, and American merchants and shippers began urging an opening of ties with Japan, a country that had virtually isolated itself from the outside world for the past 300 years. In 1853, a fleet commanded by Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived in Japan and forced the shogunate to sign a treaty with US, although Japanese fears of Russian encroachment also moved matters along.

Closer to home, Cuba was long coveted by Southerners as the choicest slave territory available. If annexed by the US and split into 3–4 states, it would restore the slave versus free state balance in Congress. President Polk had in 1845 offered the island's owner, Spain, $100 million for the island, but it was refused and Madrid made it clear that they would not part with the island under any circumstance. Southerners were not about to give up their designs on Cuba, and several filibustering expeditions were mounted. They were easily repulsed by the Spanish authorities, and the last attempt ended in fifty Americans being captured and executed for piracy, including many men from the leading families of the South. A group of enraged Southerners responded by ransacking the Spanish consulate in New Orleans.[16]

In 1854, the Spanish authorities captured the steamer Black Warrior on a technicality. War appeared to threaten, and Southerners in Congress were aggressively pushing President Pierce for it. Since the European powers were distracted with the Crimean War, there was also nobody that could come to Madrid's assistance. Meanwhile, the US ambassadors to Spain, Britain, and France met in secret in Ostend, Belgium where they proposed a "battle plan" that involved offering Spain up to $120 million for Cuba. If Madrid still refused, then US was justified in taking the island by force. However, the Ostend Manifesto soon leaked out, and an outcry from free soil Northerners forced the Pierce Administration to give up its ambitions on Cuba. Coincidentally, just as Southerners had their eye on territories in the Caribbean, Northerners in the 1850s also developed renewed designs on Canada. In the end, both sides stalemated each other and got nothing as a result.

Antislavery and abolitionism

[edit]The debate over slavery in the pre-Civil War United States has several sides. Abolitionists grew directly out of the Second Great Awakening and the European Enlightenment and saw slavery as an affront to God and/or reason. Abolitionism had roots similar to the temperance movement. The publishing of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, in 1852, galvanized the abolitionist movement.

Most debates over slavery, however, had to do with the constitutionality of the extension of slavery rather than its morality. The debates took the form of arguments over the powers of Congress rather than the merits of slavery. The result was the so-called "Free Soil Movement." Free-soilers believed that slavery was dangerous because of what it did to whites. The "peculiar institution" ensured that elites controlled most of the land, property, and capital in the South. The Southern United States was, by this definition, undemocratic. To fight the "slave power conspiracy," the nation's democratic ideals had to be spread to the new territories and the South.

In the South, however, slavery was justified in many ways. The Nat Turner Uprising of 1831 had terrified Southern whites. Moreover, the expansion of "King Cotton" into the Deep South further entrenched the institution into Southern society. John Calhoun's treatise, The Pro-Slavery Argument, stated that slavery was not simply a necessary evil but a positive good. Slavery was a blessing to so-called African savages. It civilized them and provided them with the lifelong security that they needed. Under this argument, the pro-slavery proponents believed that the African Americans were unable to take care of themselves because they were biologically inferior. Furthermore, white Southerners looked upon the North and Britain as soulless industrial societies with little culture. Whereas the North was dirty, dangerous, industrial, fast-paced, and greedy, pro-slavery proponents believed that the South was civilized, stable, orderly, and moved at a 'human pace.'

According to the 1860 U.S. census, fewer than 385,000 individuals (i.e. 1.4% of whites in the country, or 4.8% of southern whites) owned one or more slaves.[17] 95% of blacks lived in the South, comprising one-third of the population there as opposed to 1% of the population of the North.[18]

Kansas–Nebraska Act

[edit]

With the admission of California as a state in 1850, the Pacific Coast had finally been reached. Manifest Destiny had brought Americans to the end of the continent. President Millard Fillmore hoped to continue Manifest Destiny, and with this aim he sent Commodore Matthew Perry to Japan in the hopes of arranging trade agreements in 1853.

A railroad to the Pacific was planned, and Senator Stephen A. Douglas wanted the transcontinental railway to pass through Chicago. Southerners protested, insisting that it run through Texas, Southern California and end in New Orleans. Douglas decided to compromise and introduced the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854. In exchange for having the railway run through Chicago, he proposed 'organizing' (open for white settlement) the territories of Kansas and Nebraska.

Douglas anticipated Southern opposition to the act and added in a provision that stated that the status of the new territories would be subject to popular sovereignty. In theory, the new states could become slave states under this condition. Under Southern pressure, Douglas added a clause which explicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise. President Franklin Pierce supported the bill as did the South and a fraction of northern Democrats.

The act split the Whigs. Northern Whigs generally opposed the Kansas–Nebraska Act while Southern Whigs supported it. Most Northern Whigs joined the new Republican Party. Some joined the Know-Nothing Party which refused to take a stance on slavery. The southern Whigs tried different political moves, but could not reverse the regional dominance of the Democratic Party.[19]

Bleeding Kansas

[edit]With the opening of Kansas, both pro- and anti-slavery supporters rushed to settle in the new territory. Violent clashes soon erupted between them. Abolitionists from New England settled in Topeka, Lawrence, and Manhattan. Pro-slavery advocates, mainly from Missouri, settled in Leavenworth and Lecompton.

In 1855, elections were held for the territorial legislature. While there were only 1,500 legal voters, migrants from Missouri swelled the population to over 6,000. The result was that a pro-slavery majority was elected to the legislature. Free-soilers were so outraged that they set up their own delegates in Topeka. A group of pro-slavery Missourians sacked Lawrence on May 21, 1856. Violence continued for two more years until the promulgation of the Lecompton Constitution.

The violence, known as "Bleeding Kansas," scandalized the Democratic administration and began a more heated sectional conflict. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts gave a speech in the Senate entitled "The Crime Against Kansas." The speech was a scathing criticism of the South and the "peculiar institution." As an example of rising sectional tensions, days after delivering the speech, South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks approached Sumner during a recess of the Senate and caned him.

The new Republican Party

[edit]The new Republican party emerged in 1854–1856 in the North; it had minimal support in the South. Most members were former Whigs or Free Soil Democrats. The Party was ideological, with a focus on stopping the spread of slavery, and modernizing the economy through tariffs, banks, railroads and free homestead land for farmers.[20][21]

Without using the term "containment", the new Party in the mid-1850s proposed a system of containing slavery, once it gained control of the national government. Historian James Oakes explains the strategy:

- "The federal government would surround the south with free states, free territories, and free waters, building what they called a 'cordon of freedom' around slavery, hemming it in until the system's own internal weaknesses forced the slave states one by one to abandon slavery."[22]

Presidential election of 1856

[edit]

President Pierce was too closely associated with the horrors of "Bleeding Kansas" and was not renominated. Instead, the Democrats nominated former Secretary of State and current ambassador to Great Britain James Buchanan, The Know Nothing Party nominated former President Millard Fillmore, who campaigned on a platform that mainly opposed immigration and urban corruption of the sort associated with Irish Catholics. The Republicans nominated famed soldier-explorer John Frémont under the slogan of "Free soil, free labor, free speech, free men, Frémont and victory!" Frémont won most of the North and nearly won the election. A slight shift of votes in Pennsylvania and Illinois would have resulted in a Republican victory. It had a strong base with majority support in most Northern states. It dominated in New England, New York and the northern Midwest, and had a strong presence in the rest of the North. It had almost no support in the South, where it was roundly denounced in 1856–60 as a divisive force that threatened civil war.[23][24]

The election campaign was a bitter one with a high degree of personal attacks levied at all three candidates—Buchanan, aged 65, was mocked as being too old to be president and for not being married. Fremont was ridiculed for being born out of wedlock to a teenage mother. More damaging to the latter was the accusation by Know-Nothings that he was a secret Roman Catholic. Some Southern leaders threatened secession if a "free soiler" Northern candidate were elected. The two-year-old Republican Party nonetheless had a strong showing in its first presidential contest, and might have won except for Fillmore.[25]

An uninspiring figure, Buchanan won the election with 174 electoral votes to Fremont's 114. Immediately following Buchanan's inauguration in March 1857, there was a sudden depression, known as the Panic of 1857, which weakened the credibility of the Democratic Party further. He feuded incessantly with Stephen Douglas for control of the Democratic Party, while the Republicans remained united and the Fillmore's third party collapsed.[26]

Dred Scott decision

[edit]On March 6, 1857, a mere two days after Buchanan's inauguration, the Supreme Court handed down the infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford decision. Dred Scott, a slave, had lived with his master for a few years in Illinois and Wisconsin, and with the support of abolitionist groups, was now suing for his freedom on the grounds that he resided in a free state. The Supreme Court quickly ruled on the very obvious—that slaves were not US citizens and thus had no right to sue in a Federal court. It also ruled that since slaves were private property, their master was fully within his rights to reclaim runaways, even if they were in a state where slavery did not exist, on the grounds that the Fifth Amendment forbade Congress to deprive a citizen of his property without due process of law. Furthermore, the Supreme Court decided that the Missouri Compromise, which had been replaced a few years earlier by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, had always been unconstitutional and Congress had no authority to restrict slavery within a territory, regardless of its citizens' wishes.[27]

The decision outraged Northern opponents of slavery such as Abraham Lincoln and lent substance to the Republican charge that a Slave Power controlled the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court had sanctioned the hardline Southern view. This emboldened Southerners to demand even more rights for slavery, just as Northern opposition hardened. Anti-slavery speakers protested that the Supreme Court could merely interpret law, not make it, and thus the Dred Scott Decision could not legally open a territory to slavery.[28]

Lincoln-Douglas debates

[edit]The seven famous Lincoln-Douglas debates were held for the Senatorial election in Illinois between incumbent Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln, whose political experience was limited to a single term in Congress that had been mainly notable for his opposition to the Mexican War. The debates are remembered for their relevance and eloquence.

Lincoln was opposed to the extension of slavery into any new territories. Douglas, however, believed that the people should decide the future of slavery in their own territories. This was known as popular sovereignty. Lincoln, however, argued that popular sovereignty was pro-slavery since it was inconsistent with the Dred Scott Decision. Lincoln said that Chief Justice Roger Taney was the first person who said that the Declaration of Independence did not apply to blacks and that Douglas was the second. In response, Douglas came up with what is known as the Freeport Doctrine. Douglas stated that while slavery may have been legally possible, the people of the state could refuse to pass laws favourable to slavery.

In his famous "House Divided Speech" in Springfield, Illinois, Lincoln stated:

- "A house divided against itself cannot stand." I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved. I do not expect the house to fall, but I do expect that it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest further the spread of it and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward until it shall become alike lawful in all the states, old as well as new, North as well as South.[29]

During the debates, Lincoln argued that his speech was not abolitionist, writing at the Charleston debate that:

- I am not in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office.[30]

The debates attracted thousands of spectators and featured parades and demonstrations. Lincoln ultimately lost the election but vowed:

- The fight must go on. The cause of civil liberty must not be surrendered at the end of one or even 100 defeats.[31]

John Brown's raid

[edit]The debate took a new, violent turn with the actions of an abolitionist from Connecticut. John Brown was a militant abolitionist who advocated guerrilla warfare to combat pro-slavery advocates. Receiving arms and financial aid from a group of prominent Massachusetts business and social leaders known collectively as the Secret Six, Brown participated in the violence of Bleeding Kansas and directed the Pottawatomie massacre on May 24, 1856, in response to the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas. In 1859, Brown went to Virginia to liberate slaves. On October 17, Brown seized the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. His plan was to arm slaves in the surrounding area, creating a slave army to sweep through the South, attacking slaveowners and liberating slaves. Local slaves did not rise up to support Brown. He killed five civilians and took hostages. He also stole a sword that Frederick the Great had given George Washington. He was captured by an armed military force under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee. He was tried for treason to the Commonwealth of Virginia and hanged on December 2, 1859. On his way to the gallows, Brown handed a jailkeeper a note, chilling in its prophecy, predicting that the "sin" of slavery would never be cleansed from the United States without bloodshed.[32]

The raid on Harper's Ferry horrified Southerners who saw Brown as a criminal, and they became increasingly distrustful of Northern abolitionists who celebrated Brown as a hero and a martyr.

Presidential election of 1860

[edit]

The Democratic National Convention for the Election of 1860 was held in Charleston, South Carolina, despite it usually being held in the North. When the convention endorsed the doctrine of popular sovereignty, 50 Southern delegates walked out. The inability to come to a decision on who should be nominated led to a second meeting in Baltimore, Maryland. At Baltimore, 110 Southern delegates, led by the so-called "fire eaters," walked out of the convention when it would not adopt a platform that endorsed the extension of slavery into the new territories. The remaining Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas for the presidency. The Southern Democrats held a convention in Richmond, Virginia, and nominated John Breckinridge. Both claimed to be the true voice of the Democratic Party.

Former Know Nothings and some Whigs formed the Constitutional Union Party which ran on a platform based around supporting only the Constitution and the laws of the land.

Abraham Lincoln won the support of the Republican National Convention after it became apparent that William Seward had alienated certain branches of the Republican Party. Moreover, Lincoln had been made famous in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates and was well known for his eloquence and his moderate position on slavery.

Lincoln won a majority of votes in the electoral college, but only won two-fifths of the popular vote. The Democratic vote was split three ways and Lincoln was elected as the 16th president of the United States.

Secession

[edit]Lincoln's election in November led to a declaration of secession by South Carolina on December 20, 1860. Before Lincoln took office in March 1861, six other states had declared their secession from the Union: Mississippi (January 9, 1861), Florida (January 10), Alabama (January 11), Georgia (January 19), Louisiana (January 26), and Texas (February 1).

Men from both North and South met in Virginia to try to hold together the Union, but the proposals for amending the Constitution were unsuccessful. In February 1861, the seven states met in Montgomery, Alabama, and formed a new government: the Confederate States of America. The first Confederate Congress was held on February 4, 1861, and adopted a provisional constitution. On February 8, 1861, Jefferson Davis was nominated President of the Confederate States.

Civil War

[edit]

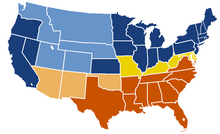

The Confederacy: brown

*territories in light shades

On April 12, 1861, after President Lincoln refused to give up Fort Sumter, the federal base in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, the new Confederate government under President Jefferson Davis ordered General P.G.T. Beauregard to open fire on the fort. It fell two days later, without casualty, spreading the flames of war across America. Immediately, rallies were held in every town and city, north and south, demanding war. Lincoln called for troops to retake lost federal property, which meant an invasion of the South. In response, four more states seceded: Virginia (April 17, 1861), Arkansas (May 6, 1861), Tennessee (May 7, 1861), and North Carolina (May 20, 1861). The four remaining slave states, Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky, under heavy pressure from the Federal government did not secede; Kentucky tried, and failed, to remain neutral.

Each side had its relative strengths and weaknesses. The North had a larger population and a far larger industrial base and transportation system. It would be a defensive war for the South and an offensive one for the North, and the South could count on its huge geography, and an unhealthy climate, to prevent an invasion. In order for the North to emerge victorious, it would have to conquer and occupy the Confederate States of America. The South, on the other hand, only had to keep the North at bay until the Northern public lost the will to fight. The Confederacy adopted a military strategy designed to hold their territory together, gain worldwide recognition, and inflict so much punishment on invaders that the North would grow weary of the war and negotiate a peace treaty that would recognize the independence of the CSA. The only point of seizing Washington, or invading the North (besides plunder) was to shock Yankees into realizing they could not win. The Confederacy moved its capital from a safe location in Montgomery, Alabama, to the more cosmopolitan city of Richmond, Virginia, only 100 miles from the enemy capital in Washington. Richmond was heavily exposed, and at the end of a long supply line; much of the Confederacy's manpower was dedicated to its defense. The North had far greater potential advantages, but it would take a year or two to mobilize them for warfare. Meanwhile, everyone expected a short war.

War in the East

[edit]

The Union assembled an army of 35,000 men (the largest ever seen in North America up to that point) under the command of General Irvin McDowell. With great fanfare, these untrained soldiers set out from Washington DC with the idea that they would capture Richmond in six weeks and put a quick end to the conflict. At the Battle of Bull Run on July 21, however, disaster ensued as McDowell's army was completely routed and fled back to the nation's capitol. Major General George McClellan of the Union was put in command of the Army of the Potomac following the battle on July 26, 1861. He began to reconstruct the shattered army and turn it into a real fighting force, as it became clear that there would be no quick, six-week resolution of the conflict. Despite pressure from the White House, McClellan did not move until March 1862, when the Peninsular Campaign began with the purpose of capturing the capitol of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia. It was initially successful, but in the final days of the campaign, McClellan faced strong opposition from Robert E. Lee, the new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. From June 25 to July 1, in a series of battles known as the Seven Days Battles, Lee forced the Army of the Potomac to retreat. McClellan was recalled to Washington and a new army assembled under the command of John Pope.

In August, Lee fought the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas) and defeated John Pope's Army of Virginia. Pope was dismissed from command and his army merged with McClellan's. The Confederates then invaded Maryland, hoping to obtain European recognition and an end to the war. The two armies met at Antietam on September 17. This was the single bloodiest day in American history. The Union victory allowed Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that all slaves in states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863 were freed. This did not actually end slavery, but it served to give a meaningful cause to the war and prevented any possibility of European intervention.

Militarily, the Union could not follow up its victory at Antietam. McClellan failed to pursue the Confederate army, and President Lincoln finally became tired of his excuses and unwillingness to fight. He was dismissed from command in October and replaced by Ambrose Burnside, despite his pleas that he was not ready for the job. He attempted to invade Richmond from the north (McClellan had tried from the east), but the campaign ended in disaster at Fredericksburg when Burnside ordered waves of futile attacks against an entrenched Confederate position. The next year also proved difficult for the Union initially. Burnside was replaced by General Joseph "Fighting Joe" Hooker in January 1863, but he proved unable to stop Lee and "Stonewall" Jackson at Chancellorsville in May. Lee's second invasion of the North, however, proved disastrous. Hooker was replaced by George Meade, and four days later the Battle of Gettysburg took place. Lee's army lost scores of irreplaceable men and would never be the same again. Abraham Lincoln was angered by George Meade's failure to pursue Lee after Gettysburg, but decided to let him stay in command, a decision endorsed by Ulysses S. Grant who was appointed General-in-Chief of all the Union armies early in 1864.

War in the West

[edit]While the Confederacy fought the Union to a bloody stalemate in the East, the Union army was much more successful in the West. Confederate insurrections in Missouri were put down by the federal government by 1863, despite the initial Confederate victory at Wilson's Creek near Springfield, Missouri. After the Battle of Perryville, the Confederates were also driven from Kentucky, resulting in a major Union victory. Lincoln once wrote of Kentucky, "I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game." The fall of Vicksburg gave the Union control of the Mississippi River and cut the Confederacy in two. Sherman's successes in Chattanooga and then Atlanta left few Confederate forces to resist his destruction of Georgia and the Carolinas. The Dakota War broke out in Minnesota in 1862.[33][34]

End of the Confederacy

[edit]In 1864, General Grant assigned himself as direct commander of Meade and the Army of the Potomac, and placed General William Sherman in command of the Western Theatre. Grant began to wage a total war against the Confederacy. He knew that the Union's strength lay in its resources and manpower and thus began to wage a war of attrition against Lee while Sherman devastated the West. Grant's Wilderness Campaign forced Lee into Petersburg, Virginia. There he waged—and with Lee, pioneered—trench warfare at the Siege of Petersburg. In the meantime, General Sherman seized Atlanta, securing President Lincoln's reelection. He then began his famous March to the Sea which devastated Georgia and South Carolina. Lee attempted to escape from Petersburg in March–April 1865, but was trapped by Grant's superior number of forces. Lee surrendered at the Appomattox Court House. Four years of bloody warfare had come to a conclusion.

Home fronts

[edit]United States

[edit]The Union began the war with overwhelming long-term advantages in manpower, industry, and financing. It took a couple years for the potential to be realized, but with the victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in July 1863, the Confederacy was doomed.

Lincoln, an ungainly giant, did not look the part of a president, but historians have overwhelmingly praised the "political genius" of his performance in the role.[35] His first priority was military victory, and that required that he master entirely new skills as a master strategist and diplomat. He supervised not only the supplies and finances, but as well the manpower, the selection of generals, and the course of overall strategy. Working closely with state and local politicians he rallied public opinion and (at Gettysburg) articulated a national mission that has defined America ever since. Lincoln's charm and willingness to cooperate with political and personal enemies made Washington work much more smoothly than Richmond. His wit smoothed many rough edges. Lincoln's cabinet proved much stronger and more efficient than Davis's, as Lincoln channeled personal rivalries into a competition for excellence rather than mutual destruction. With William Seward at State, Salmon P. Chase at the Treasury, and (from 1862) Edwin Stanton at the War Department, Lincoln had a powerful cabinet of determined men; except for monitoring major appointments, Lincoln gave them full rein to destroy the Confederacy. Malaise led to sharp Democratic gains in the 1862 off-year elections, but the Republicans kept control of Congress and the key states. Despite grumbling by Radical Republicans, who disliked Lincoln's leniency toward the South, Lincoln kept control of politics. The Republicans expanded with the addition of War Democrats and ran as the Union Party in 1864, blasting the Democrats as Copperheads and sympathizers with disunion. With the Democrats in disarray, Lincoln's ticket won in a landslide.[36]

During the Civil War the key policy-maker in Congress was Thaddeus Stevens, as chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, Republican floor leader, and spokesman for the Radical Republicans. Although he thought Lincoln was too moderate regarding slavery, he worked well with the president and Treasury Secretary in handling major legislation that funded the war effort and permanently transformed the nation's economic policies regarding tariffs, bonds, income and excise taxes, national banks, suppression of money issued by state banks, greenback currency, and western railroad land grants.[37]

Confederate States

[edit]The Confederacy was beset by growing problems as its territory steadily shrank, its people grew impoverished, and hopes of victory changed from reliance on Confederate military prowess to dreams of foreign intervention, to finally a desperate hope that the Yankees would grow so weary of war they would sue for peace.[38] The South lost its lucrative export market as the Union blockade shut down all commercial traffic, with only very expensive blockade runners getting in and out. In 1861 the South lost most of its border regions, with Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri gained for the enemy, and western Virginia broken off. The Southern transportation system depended on a river system that the Union gunboats soon dominated, as control of the Mississippi, Missouri, Cumberland, and Tennessee rivers fell to the Union in 1862–63. That meant all the river towns fell to the Union as well, and so did New Orleans in 1862. The rickety railroad system was not designed for long-distance traffic (it was meant to haul cotton to the nearest port), and it steadily deteriorated until by the end practically no trains were running. Civilian morale and recruiting held up reasonably well, as did the morale of the army, until the last year or so.[39] The Confederacy had democratic elections (for all white men), but no political parties. One result was that governors became centers of opposition to Jefferson Davis and his increasingly unpopular central administration in Richmond.[40] Financially the South was in bad shape as it lost its export market, and internal markets failed one after the other. By 1864 women in the national capital were rioting because of soaring food prices they could not afford. With so few imports available, it was necessary to make do, use ersatz (such as local beans for coffee), use up, and do without.[41] The large slave population never rose up in armed revolt, but black men typically took the first opportunity to escape to Union lines, where over 150,000 enrolled in the Union army.[42] When the end came the South had a shattered economy, 300,000 dead, hundreds of thousands wounded, and millions impoverished, but three million former slaves were now free.[43]

Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

[edit]On April 14, 1865, four days after the news of Lee's surrender reached Washington, an air of celebration pervaded the capital. That evening, President Lincoln attended a performance of Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre. During the third act, a Confederate sympathizer named John Wilkes Booth shot and killed Abraham Lincoln. As he fled the scene, he yelled "Sic semper tyrannis", the Virginia state motto. John Wilkes Booth was tracked, twelve days later, to a farm near Bowling Green, Virginia, on April 26. He was shot and killed by Union Army Sergeant Boston Corbett. His co-conspirators were tried before a military commission and were hanged on July 7.

See also

[edit]- Timeline of the history of the United States (1820–1859)

- Timeline of the history of the United States (1860–1899)

- American Civil War

- Confederate States of America

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Timeline of events leading to the American Civil War

- Timeline of the American Old West

- Union (American Civil War)

- Presidency of Zachary Taylor

- Presidency of James Buchanan

- Presidency of Abraham Lincoln

Notes

[edit]- ^ Faust, Drew Gilpin (2009) [2008]. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 274. ISBN 9780375703836.

- ^ Taylor (1962).

- ^ Craven, Avery O. (February 1953). The Growth of Southern Nationalism, 1848–1861. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807100066.

- ^ Volo, James M.; Volo, Dorothy Denneen (2000). Encyclopedia of the Antebellum South. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780313308864.

- ^ Stover, John F. (1997). American Railroads. University of Chicago Press. pp. 35–95. ISBN 9780226776606.

- ^ Marrs, Aaron W. (2009). Railroads in the Old South: Pursuing Progress in a Slave Society. JHU Press. ISBN 9780801898457.

- ^ Licht (1995), p. 21–45.

- ^ Gordon, John Steele (2004). An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Economic Power. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780060093624.

- ^ Eric Foner, "The Wilmot Proviso Revisited." Journal of American History 56.2 (1969): 262–279. online Archived 2022-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Christopher Childers, "Interpreting Popular Sovereignty: A Historiographical Essay," Civil War History 57#1 (2011) pp. 48–70 online Archived 2023-01-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cowan, Jill (June 19, 2019). "'It's Called Genocide': Newsom Apologizes to the State's Native Americans". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- ^ Madley, Benjamin (2016). An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300230697.

- ^ Thornton, Russell (1990). American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History since 1492. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 107–109.

- ^ Brands, H.W. (2002). The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream. Doubleday. ISBN 9780385502160.

- ^ Bordewich, Fergus M. (2012). America's Great Debate: Henry Clay, Stephen A. Douglas, and the Compromise That Preserved the Union. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439141687.

- ^ Zemler, Jeffrey A. (May 1983). The Texas Press and the Filibusters of the 1850s: Lopez, Carajal, and Walker (PDF) (Thesis). Denton, Texas. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-03. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- ^ Olsen, O.H. (December 2004). "Historians and the extent of slave ownership in the Southern United States". Civil War History. 50 (4): 401–417. doi:10.1353/cwh.2004.0074. S2CID 143943479. Archived from the original on July 20, 2007 – via southernhistory.net.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (18 April 1996). Drawn with the Sword. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 15. ISBN 9780195096798.

- ^ Holt, Michael (2004). The Fate of Their Country: Politicians, Slavery Extension, and the Coming of the Civil War. New York. ISBN 9780809095186.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gould, Lewis (2003). Grand Old Party: A History of the Republicans. Random House. ISBN 9780375507410.

- ^ Gienapp, William E. (1987). The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780198021148.

- ^ Oakes, James (2013). Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 12. ISBN 9780393065312. Archived from the original on 2023-01-20. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Gould, Lewis (2003). "1". Grand Old Party: A History of the Republicans. Random House. ISBN 9780375507410.

- ^ Nichols, Roy F.; Klein, Philip S. (1971). Schlesinger, Arthur Jr. (ed.). The Election of 1856. Vol. 5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Howard, Victor B. (1971). "The 1856 Election in Ohio: Moral Issues in Politics". Ohio History. 80 (1).

- ^ Nichols, Roy F. (1948). The Disruption of American Democracy. Macmillan Company. ISBN 9780608039565.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (2007). "Scott v. Sandford: The Court's Most Dreadful Case and How it Changed History" (PDF). Chicago-Kent Law Review. 82 (3): 3–48. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2012.

- ^ Potter, David M. (1976). The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861. Harper Collins. pp. 267–296. ISBN 9780061319297.

- ^ Hanson, Henry (1962). The Civil War: A History. New York. p. 29. ISBN 9780451603326.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hanson (1962), p. 30.

- ^ Hanson (1962), p. 31.

- ^ Faust, Patricia L. (1986). Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780061812613. Archived from the original on 2000-04-12. Retrieved 2021-03-16 – via civilwarhome.com/johnbrownbio.htm.

- ^ Kunnen-Jones, Marianne (August 21, 2002). "Anniversary Volume Gives New Voice To Pioneer Accounts of Sioux Uprising". University of Cincinnati. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Tolzmann, Don Heinrich (2002). German Pioneer Accounts of the Great Sioux Uprising of 1862. Little Miami Publishing Company. ISBN 9780971365766.

- ^ Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2005). Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684824901.

- ^ Paludan, Phillip Shaw (1994). The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kansas. pp. 21–48. ISBN 9780700606719.

- ^ Richardson, Heather Cox (1997). The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies During the Civil War. Harvard University Press. pp. 9, 41, 52, 111, 116, 120, 182, 202. ISBN 9780674059658.

- ^ Gallagher, Gary W. (September 2009). "Disaffection, Persistence, and Nation: Some Directions in Recent Scholarship on the Confederacy". Civil War History. 55 (3): 329–353. doi:10.1353/cwh.0.0065. S2CID 144977161.

- ^ Davis, William C. (2002). Look Away! A History of the Confederate States of America. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743227711.

- ^ Rable, George C. (1994). The Confederate Republic: A Revolution against Politics. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807821442.

- ^ Massey, Mary (1993). Ersatz in the Confederacy: shortages and substitutes on the southern homefront. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9780872498778.

- ^ Yacovone, Donald; Fuller, Charles (2004). Freedom's Journey: African American Voices of the Civil War. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781556525216.

- ^ Rubin, Anne Sarah (2005). A Shattered Nation. doi:10.5149/9780807888957_rubin. ISBN 9780807829288.

Further reading

[edit]- Beringer, Richard E.; Jones, Archer; Still, William N.; Hattaway, Herman (1988). The Elements of Confederate Defeat: Nationalism, War Aims, and Religion. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820310770.

- Burton, Vernon O. (2007) [2006]. The Age of Lincoln. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780809095131.

- Catton, Bruce (1971) [1960]. The Civil War. ISBN 9780070102668.

- Cheathem, Mark R.; Terry, Corps (2016). Historical Dictionary of the Jacksonian Era and Manifest Destiny (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442273207.

- Donald, David Herbert; Randall, James Garfield; et al. (et al.) (2001) [1937]. The Civil War and Reconstruction. Norton. ISBN 9780393974270.

- Fellman, Michael; et al. (et al.) (2007). This Terrible War: The Civil War and its Aftermath (2nd ed.). Longman. ISBN 9780321125583.

- Goldfield, David (2011). America Aflame: How the Civil War Created a Nation. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9781608193745.

- Guelzo, Allen C. (2012). Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780199843282.

- Licht, Walter (1995). Industrializing America: The Nineteenth Century. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801850141.

- Litwack, Leon F. (1979). Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery. Knopf. ISBN 9780394500997.

- McPherson, James M.; et al. (et al.) (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. ISBN 9780195038637.

- Murray, Williamson; Wei-siang Hsieh, Wayne (2016). A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691169408.

- Nevins, Allan (1992) [1947]. Ordeal of the Union. Collier Books. ISBN 9780020354451.

- Paludan, Phillip Shaw (1996). A People's Contest: The Union and Civil War 1861–1865. ISBN 9780060159030.

- Potter, David M. (1976). The Impending Crisis, America Before the Civil War, 1848-1861. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780061319297.

- Resch, John, ed. (2004). Americans at War: Society, Culture, and the Homefront. Macmillan Reference USA.

- Ford Rhodes, James (2012) [1917]. A History of the Civil War, 1861–1865. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486137780.

- Rubin, Anne S. (2005). A Shattered Nation: The Rise & Fall of the Confederacy 1861–1868. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807829288.

- Sheehan-Dean, Aaron (ed.). A Companion to the U.S. Civil War. New York. ISBN 9781444351316.

- Silbey, Joel H. (6 January 2014). A Companion to the Antebellum Presidents 18371861. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118609293.

- Taylor, George Rogers (1962) [1951]. The Transportation Revolution, 1815–1860. ISBN 9780873321013.

- Ward, Geoffrey C.; Burns, Ken; Burns, Ric (1990). The Civil War. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 9780679742777.

External links

[edit]- "On the Eve of War: North vs. South" lesson plan for grades 9–12 from National Endowment for the Humanities "EDSITEMENT" series