Oboe

| |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 422.112-71 (Double-reeded aerophone with keys) |

| Developed | Mid 17th century from the shawm |

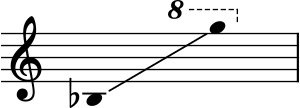

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

The oboe (/ˈoʊboʊ/ OH-boh) is a type of double-reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites.

The most common type of oboe, the soprano oboe pitched in C, measures roughly 65 cm (25+1⁄2 in) long and has metal keys, a conical bore and a flared bell. Sound is produced by blowing into the reed at a sufficient air pressure, causing it to vibrate with the air column.[1] The distinctive tone is versatile and has been described as "bright".[2] When the word oboe is used alone, it is generally taken to mean the soprano member rather than other instruments of the family, such as the bass oboe, the cor anglais (English horn), or oboe d'amore.

Today, the oboe is commonly used as orchestral or solo instrument in symphony orchestras, concert bands and chamber ensembles. The oboe is especially used in classical music, film music, some genres of folk music, and is occasionally heard in jazz, rock, pop, and popular music. The oboe is widely recognized as the instrument that tunes the orchestra with its distinctive 'A'.[3]

A musician who plays the oboe is called an oboist.

Sound

[edit]In comparison to other modern woodwind instruments, the soprano oboe is sometimes referred to as having a "bright and penetrating" voice.[4][5] The Sprightly Companion, an instruction book published by Henry Playford in 1695, describes the oboe as "Majestical and Stately, and not much Inferior to the Trumpet".[6] In the play Angels in America the sound is described as like "that of a duck if the duck were a songbird".[7] The rich timbre is derived from its conical bore (as opposed to the generally cylindrical bore of flutes and clarinets). As a result, oboes are easier to hear over other instruments in large ensembles due to its penetrating sound.[8] The highest note is a semitone lower than the nominally highest note of the B♭ clarinet. Since the clarinet has a wider range, the lowest note of the B♭ clarinet is significantly deeper (a minor sixth) than the lowest note of the oboe.[9]

Music for the standard oboe is written in concert pitch (i.e., it is not a transposing instrument), and the instrument has a soprano range, usually from B♭3 to G6. Orchestras tune to a concert A played by the first oboe.[10] According to the League of American Orchestras, this is done because the pitch is secure and its penetrating sound makes it ideal for tuning.[11] The pitch of the oboe is affected by the way in which the reed is made. The reed has a significant effect on the sound. Variations in cane and other construction materials, the age of the reed, and differences in scrape and length all affect the pitch. German and French reeds, for instance, differ in many ways, causing the sound to vary accordingly. Weather conditions such as temperature and humidity also affect the pitch. Skilled oboists adjust their embouchure to compensate for these factors. Subtle manipulation of embouchure and air pressure allows the oboist to express timbre and dynamics.

Reeds

[edit]

The oboe uses a double reed, similar to that used for the bassoon.[12] Most professional oboists make their reeds to suit their individual needs. By making their reeds, oboists can precisely control factors such as tone color, intonation, and responsiveness. They can also account for individual embouchure, oral cavity, oboe angle, and air support.

Novice oboists rarely make their own reeds, as the process is difficult and time-consuming, and frequently purchase reeds from a music store instead. Commercially available cane reeds are available in several degrees of hardness; a medium reed is very popular, and most beginners use medium-soft reeds. These reeds, like clarinet, saxophone, and bassoon reeds, are made from Arundo donax. As oboists gain more experience, they may start making their own reeds after the model of their teacher or buying handmade reeds (usually from a professional oboist) and using special tools including gougers, pre-gougers, guillotines, shaper tips, knives, and other tools to make and adjust reeds to their liking.[13] The reed is considered the part of oboe that makes the instrument so difficult because the individual nature of each reed means that it is hard to achieve a consistent sound. Slight variations in temperature, humidity, altitude, weather, and climate can also have an effect on the sound of the reed, as well as minute changes in the physique of the reed.[14]

Oboists often prepare several reeds to achieve a consistent sound, as well as to prepare for environmental factors such as chipping of a reed or other hazards. Oboists may have different preferred methods for soaking their reeds to produce optimal sounds; the most preferred method tends to be to soak the oboe reed in water before playing.[15]

Plastic oboe reeds are rarely used, and are less readily available than plastic reeds for other instruments, such as the clarinet. However, they do exist, and are produced by brands such as Legere.[16]

History

[edit]Centuries before the Spanish and Portuguese conquests in the New World, the early version of the chirimía arrived in Europe from the Middle East due to cultural exchanges. The Crusades brought Europeans into contact with the Turko-Arabic zurna. However, the oboe’s roots go back even further, linked to ancient reed instruments like those of Egypt and Mesopotamia, as well as the Greek aulos and Roman tibia. Nearly lost in the West during the Dark Ages, the oboe reappeared with the Arabic zurna in the 13th century, evolving through European bagpipes and finally becoming the French hautbois in the 17th century, which is when modern oboe history truly began.[17] In English, prior to 1770, the standard instrument was called a hautbois, hoboy, or French hoboy (/ˈhoʊbɔɪ/ HOH-boy). This was borrowed from the French name, hautbois [obwɑ], which is a compound word made up of haut ("high", "loud") and bois ("wood", "woodwind").[18] The French word means 'high-pitched woodwind' in English. The spelling of oboe was adopted into English c. 1770 from the Italian oboè, a transliteration of the 17th-century pronunciation of the French name.

The regular oboe first appeared in the mid-17th century, when it was called a hautbois. This name was also used for its predecessor, the shawm, from which the basic form of the hautbois was derived.[19] Major differences between the two instruments include the division of the hautbois into three sections, or joints (which allowed for more precise manufacture), and the elimination of the pirouette, the wooden ledge below the reed which allowed players to rest their lips.

The exact date and location of origin of the hautbois are obscure, as are the inventors. Circumstantial evidence, such as the statement by the flautist composer Michel de la Barre in his Memoire, points to members of the Philidor (Filidor) and Hotteterre families. The instrument may in fact have had multiple inventors.[20] The hautbois quickly spread throughout Europe, including Great Britain, where it was called hautboy, hoboy, hautboit, howboye, and similar variants of the French name.[21] It was the main melody instrument in early military bands, until it was succeeded by the clarinet.[22]

The standard Baroque oboe is generally made of boxwood and has three keys: a "great" key and two side keys (the side key is often doubled to facilitate use of either the right or left hand on the bottom holes). In order to produce higher pitches, the player has to "overblow", or increase the air stream to reach the next harmonic. Notable oboe-makers of the period are the Germans Jacob Denner and J.H. Eichentopf, and the English Thomas Stanesby (died 1734) and his son Thomas Jr (died 1754). The range for the Baroque oboe comfortably extends from C4 to D6. In the mid-20th century, with the resurgence of interest in early music, a few makers began producing copies to specifications taken from surviving historical instruments.

Classical

[edit]The Classical period brought a regular oboe whose bore was gradually narrowed, and the instrument became outfitted with several keys, among them those for the notes D♯, F, and G♯. A key similar to the modern octave key was also added called the "slur key", though it was at first used more like the "flick" keys on the modern German bassoon.[23] Only later did French instrument makers redesign the octave key to be used in the manner of the modern key (i.e. held open for the upper register, closed for the lower). The narrower bore allows the higher notes to be more easily played, and composers began to use the oboe's upper register more often in their works. Because of this, the oboe's tessitura in the Classical era was somewhat broader than that found in Baroque works. The range for the Classical oboe extends from C4 to F6 (using the scientific pitch notation system), though some German and Austrian oboes are capable of playing one half-step lower.

Several Classical-era composers wrote concertos for oboe. Mozart composed both the solo concerto in C major K. 314/285d and the lost original of Sinfonia Concertante in E♭ major K. 297b, as well as a fragment of F major concerto K. 417f. Haydn wrote both the Sinfonia Concertante in B♭ Hob. I:105 and the spurious concerto in C major Hob. VIIg:C1. Beethoven wrote the F major concerto, Hess 12, of which only sketches survive, though the second movement was reconstructed in the late 20th century). Numerous other composers including Johann Christian Bach, Johann Christian Fischer, Jan Antonín Koželuh, and Ludwig August Lebrun also composed pieces for the oboe. Many solos exist for the regular oboe in chamber, symphonic, and operatic compositions from the Classical era.

Wiener oboe

[edit]The Wiener oboe (Viennese oboe) is a type of modern oboe that retains the essential bore and tonal characteristics of the historical oboe. The Akademiemodel Wiener Oboe, first developed in the late 19th century by Josef Hajek from earlier instruments by C. T. Golde of Dresden (1803–73), is now made by several makers such as André Constantinides, Karl Rado, Guntram Wolf, Christian Rauch and Yamaha. It has a wider internal bore, a shorter and broader reed and the fingering-system is very different from the conservatoire oboe.[24] In The Oboe, Geoffrey Burgess and Bruce Haynes write "The differences are most clearly marked in the middle register, which is reedier and more pungent, and the upper register, which is richer in harmonics on the Viennese oboe".[25] Guntram Wolf describes them: "From the concept of the bore, the Viennese oboe is the last representative of the historical oboes, adapted for the louder, larger orchestra, and fitted with an extensive mechanism. Its great advantage is the ease of speaking, even in the lowest register. It can be played very expressively and blends well with other instruments."[26] The Viennese oboe is, along with the Vienna horn, perhaps the most distinctive member of the Wiener Philharmoniker instrumentarium.

Conservatoire oboe

[edit]This oboe was developed further in the 19th century by the Triébert family of Paris. Using the Boehm flute as a source of ideas for key work, Guillaume Triébert and his sons, Charles and Frederic, devised a series of increasingly complex yet functional key systems. A variant form using large tone holes, the Boehm system oboe, was never in common use, though it was used in some military bands in Europe into the 20th century. F. Lorée of Paris made further developments to the modern instrument. Minor improvements to the bore and key work have continued through the 20th century, but there has been no fundamental change to the general characteristics of the instrument for several decades.[27]

Modern oboe

[edit]The modern standard oboe is most commonly made from grenadilla, also known as African blackwood, although some manufacturers also make oboes out of other species of the genus Dalbergia, which includes cocobolo, rosewood, and violetwood (also known as kingwood). Ebony (genus Diospyros) has also been used. Student model oboes are often made from plastic resin to make the instrument cheaper and more durable.

The oboe has an extremely narrow conical bore. It is played with a double reed consisting of two thin blades of cane tied together on a small-diameter metal tube (staple) which is inserted into the reed socket at the top of the instrument. The commonly accepted range for the oboe extends from B♭3 to about G6, over two and a half octaves, though its common tessitura lies from C4 to E♭6. Some student oboes do not have a B♭ key and only extend down to B3.

A modern oboe with the "full conservatoire" ("conservatory" in the US) or Gillet key system has 45 pieces of keywork, with the possible additions of a third-octave key and alternate (left little finger) F- or C-key. The keys are usually made of nickel silver, and are silver- or occasionally gold-plated. Besides the full conservatoire system, oboes are also made using the British thumbplate system. Most have "semi-automatic" octave keys, in which the second-octave action closes the first, and some have a fully automatic octave key system, as used on saxophones. Some full-conservatory oboes have finger holes covered with rings rather than plates ("open-holed"), and most of the professional models have at least the right-hand third key open-holed. Professional oboes used in the UK and Iceland frequently feature conservatoire system combined with a thumb plate. Releasing the thumb plate has the same effect as pressing down the right-hand index-finger key. This produces alternate options which eliminate the necessity for most of the common cross-intervals (intervals where two or more keys need to be released and pressed down simultaneously), as cross-intervals are much more difficult to execute in such a way that the sound remains clear and continuous throughout the frequency change (a quality also called legato and often called for in the oboe repertoire).

Other members of the oboe family

[edit]

The standard oboe has several siblings of various sizes and playing ranges. The most widely known and used today is the cor anglais (English horn) the tenor (or alto) member of the family. A transposing instrument; it is pitched in F, a perfect fifth lower than the oboe. The oboe d'amore, the alto (or mezzo-soprano) member of the family, is pitched in A, a minor third lower than the oboe. J.S. Bach made extensive use of both the oboe d'amore as well as the taille and oboe da caccia, Baroque antecedents of the cor anglais.

Less common is the bass oboe (also called baritone oboe), which sounds one octave lower than the oboe. Delius, Strauss and Holst scored for the instrument.[28]

Similar to the bass oboe is the more powerful heckelphone, which has a wider bore and larger tone than the baritone oboe. Only 165 heckelphones have ever been made. Competent heckelphone players are difficult to find due to the extreme rarity of this particular instrument.[29]

The least common of all are the musette (also called oboe musette or piccolo oboe), the sopranino member of the family (it is usually pitched in E♭ or F above the oboe), and the contrabass oboe (typically pitched in C, two octaves deeper than the standard oboe).

Folk versions of the oboe, sometimes equipped with extensive keywork, are found throughout Europe. These include the musette (France) and the piston oboe and bombarde (Brittany), the piffero and ciaramella (Italy), and the xirimia (also spelled chirimia) (Spain). Many of these are played in tandem with local forms of bagpipe, particularly with the Italian müsa and zampogna or Breton biniou.

David Stock's concerto "Oborama" features the Oboe and its other members as a soloist, the instrument changing in each movement. (ex. Oboe D'amore in movement 3 and Bass Oboe in movement 4)

Notable classical works featuring the oboe

[edit]- Tomaso Albinoni, Oboe (and two-oboe) Concerti

- Georg Philipp Telemann, oboe concerti and sonatas, trio sonatas for oboe, recorder, and basso continuo

- Antonio Vivaldi, at least 15 oboe concertos

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Brandenburg concertos nos. 1 and 2, Concerto for violin and oboe, lost oboe concerti, numerous oboe obbligato lines in the sacred and secular cantatas

- Tchaikovsky, theme to Swan Lake

- Samuel Barber, Canzonetta, op. 48, for oboe and string orchestra (1977–78, orch. completed by Charles Turner)

- Vincenzo Bellini, Concerto in E-flat, for oboe and chamber orchestra consisting of two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, tho bassoons, two French horns, and strings (before 1825)

- Luciano Berio, Chemins IV (on Sequenza VII), for oboe and string orchestra (1975)

- Harrison Birtwistle, An Interrupted Endless Melody, for oboe and piano (1991)

- Harrison Birtwistle, Pulse Sampler, for oboe and claves (1981)

- Benjamin Britten, Temporal Variations, Two Insect Pieces, Phantasy Quartet, op. 2

- Howard J. Buss, Sonatina of Remembrance, for oboe and piano (2023)

- Elliott Carter, Oboe Concerto (1986–87); Trilogy, for oboe and harp (1992); Quartet for oboe, violin, viola, and cello (2001)

- Morton Feldman, Oboe and Orchestra (1976)

- Vivian Fine, Sonatina for Oboe and Piano (1939)

- Domenico Cimarosa, Oboe Concerto in C major (arranged)

- John Corigliano, Oboe Concerto (1975)

- Miguel del Águila, Summer Song for oboe and piano

- Antal Doráti, Duo Concertante for Oboe and Piano

- Madeleine Dring, Three Piece Suite (arr. Roger Lord)

- Madeleine Dring, Trio for oboe, flute and piano

- Henri Dutilleux, Les Citations for oboe, harpsichord, double bass and percussion (1991)

- Eric Ewazen, Down a River of Time, oboe and string orchestra (1999)

- Eugene Aynsley Goossens, Concerto for Oboe, Op. 45 (1928)

- Edvard Grieg, Symphonic Dances Op. 64, no. 2

- George Frideric Handel, "The Arrival of the Queen of Sheba", Oboe Concerto No. 1, No. 2, No. 3 and oboe sonatas HWV 257, 263a, 266

- Joseph Haydn (doubtful, possibly by Ignaz Malzat), Oboe Concerto in C major

- Hans Werner Henze, Doppio concerto, for oboe, harp, and string orchestra (1966)

- Jennifer Higdon, Oboe Concerto, 2005

- Paul Hindemith, Sonata for Oboe and Piano

- Heinz Holliger, Mobile, for oboe and harp (1962); Trio, for oboe (doubling English horn), viola, and harp (1966); Sechs Stücke, for oboe (doubling oboe d'amore) and harp (1998–99)

- Charles Koechlin Sonata for Oboe and Piano, Op. 58

- Antonio Lotti, Concerto for oboe d'amore

- Witold Lutosławski, Double Concerto for Oboe, Harp, and Chamber Orchestra

- Bruno Maderna, 3 oboe concertos (1962–63) (1967) (1973); Grande aulodia, for flute, oboe, and orchestra (1970), Aulodia for Oboe d'amore (and guitar ad Libitum)

- Alessandro Marcello, Concerto in D minor

- Bohuslav Martinů, Concerto for Oboe and Small Orchestra

- Olivier Messiaen, Concert à quatre

- Darius Milhaud, Les rêves de Jacob, op. 294, for oboe, violin, viola, cello, and doublebass (1949); Sonatina, op. 337, for oboe and piano (1954)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Oboe Concerto in C major, Quartet in F major for oboe, violin, viola, and cello

- Carl Nielsen, Two Fantasy Pieces for Oboe and Piano, op. 2

- Antonio Pasculli, oboe concertos for oboe and piano/orchestra

- Francis Poulenc, Oboe Sonata

- Sergei Prokofiev, Quintet for Oboe, Clarinet, Violin, Viola and Bass op. 39 (1923)

- Sergei Prokofiev, Peter and the Wolf, the duck

- Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin

- Edmund Rubbra, Oboe Sonata

- Camille Saint-Saëns, Sonata for Oboe and Piano in D Major

- Robert Schumann, Three Romances for Oboe and Piano

- Karlheinz Stockhausen, In Freundschaft, for oboe, Nr. 46⅔, Wednesday from Light for oboe and electronic music (from Orchester-Finalisten, scene 2 of Mittwoch aus Licht)

- Richard Strauss, Oboe Concerto

- Igor Stravinsky, Pastorale (transcribed in 1933 for Violin and Wind Quartet)

- Bernd Alois Zimmermann, Concerto for Oboe and Small Orchestra (1952)

- Toru Takemitsu, Distance for Oboe and Shō [ad lib.] (1971)

- Toru Takemitsu, Entre-Temps for Oboe and String Quartett (1981)

- Joan Tower, Island Prelude (1988)

- Isang Yun, Concerto for Oboe (Oboe d'amore) and Orchestra (1990)

- Josef Tal, Duo for oboe & English horn (1992)

- Ralph Vaughan Williams, Concerto for Oboe and Strings, Ten Blake Songs for oboe and tenor

- John Woolrich, Oboe Concerto (1996)

- Jan Dismas Zelenka (1723) Concertanti, Oboe Trios and other works[30]

- Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, Oboe Concerto

- Flor Alpaerts, Concertstuk for Oboe and Piano

- Lior Navok Fizzy, for oboe and piano (2018)

Unaccompanied pieces

[edit]- Benjamin Britten, Six Metamorphoses after Ovid, Op. 49 (1951)

- Carlos Chávez, Upingos (1957)

- Eugene Aynsley Goossens, Islamite Dance (1962); Searching For Lambs, Op. 49 (1930); When Thou Art Dead, Op. 43 (1926)

- Luciano Berio, Sequenza VII (1969)

- Isang Yun, Piri (1971)

- Antal Doráti, Five Pieces for Solo Oboe (1980)

- Heinz Holliger, Sonata, for unaccompanied oboe (1956–57/99); Studie über Mehrklänge, for unaccompanied oboe (1971)

- Peter Maxwell Davies, First Grace of Light (1991)

- John Palmer, Hinayana (1999), including extended techniques[31]

Use in non-classical music

[edit]Jazz

[edit]The oboe remains uncommon in jazz music, but there have been notable uses of the instrument. Some early bands in the 1920s and 1930s, most notably that of Paul Whiteman, included it for coloristic purposes. Most often in this era it was used for dance band music, but occasionally oboists may be heard used in a similar manner to a saxophone for solos. Most of the time these oboists were already playing with the band or orchestra on a different woodwind instrument. The multi-instrumentalist Garvin Bushell (1902–1991) played the oboe in jazz bands as early as 1924 and used the instrument throughout his career, eventually recording with John Coltrane in 1961.[32] Gil Evans featured oboe in sections of his famous Sketches of Spain collaboration with trumpeter Miles Davis. Though primarily a tenor saxophone and flute player, Yusef Lateef was among the first (in 1961) to use the oboe as a solo instrument in modern jazz performances and recordings. Composer and double bassist Charles Mingus gave the oboe a brief but prominent role (played by Dick Hafer) in his composition "I.X. Love" on the 1963 album Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus.

With the birth of jazz fusion in the late 1960s, and its continuous development through the following decade, the oboe became somewhat more prominent, replacing on some occasions the saxophone as the focal point. The oboe was used with great success by the Welsh multi-instrumentalist Karl Jenkins in his work with the groups Nucleus and Soft Machine, and by the American woodwind player Paul McCandless, co-founder of the Paul Winter Consort and later Oregon.

The 1980s saw an increasing number of oboists try their hand at non-classical work, and many players of note have recorded and performed alternative music on oboe. Some present-day jazz groups influenced by classical music, such as the Maria Schneider Orchestra, feature the oboe.[33]

Rock and pop

[edit]Indie singer-songwriter and composer Sufjan Stevens, having studied the instrument in school, often includes the instrument in his arrangements and compositions, most frequently in his geographic tone-poems Illinois, Michigan.[34] Peter Gabriel played the oboe while he was a member of Genesis, most prominently on "The Musical Box".[35] Andy Mackay of Roxy Music plays oboe, sometimes with a Wah-Wah pedal.

Film music

[edit]The oboe is frequently featured in film music, often to underscore a particularly poignant or emotional scene. An example is the 1989 film Born on the Fourth of July. One of the most prominent uses of the oboe in a film score is Ennio Morricone's "Gabriel's Oboe" theme from the 1986 film The Mission.

It is featured as a solo instrument in the theme "Across the Stars" from the John Williams score to the 2002 film Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones.[36]

The oboe is also featured as a solo instrument in the "Love Theme" in Nino Rota's score to The Godfather (1972).[37]

Notable oboists

[edit]Manufacturers

[edit]- Barrington Instruments Inc. (Barrington, Illinois, US)

- Boosey & Hawkes (1851–1970s) (London, UK)

- Buffet Crampon (Mantes-la-Ville, France)

- Bulgheroni (Parè, Italy)

- Cabart or Thibouville-Cabart (1869–1974, bought out by F. Lorée) (Paris, France)

- Carmichael (UK)

- Chauvet (until ~ 1975) (Paris, France)

- Mark Chudnow (MCW, Sierra) (Napa, California, US)

- Constantinides (Pöggstall, Austria)

- Covey (Blairsville, Georgia, US)

- Dupin (Moutfort, Luxembourg)

- D.W.K (Seoul, Korea)

- Fossati (incl. Tiery) (Paris, France)

- Fox (South Whitley, Indiana, US)

- Frank (Berlin, Germany)

- Graessel (Nürnberg, Germany)

- Heckel (until the 1960s) (Wiesbaden, Germany)

- Thomas Hiniker Woodwinds (Rochester, Minnesota, US)

- TW Howarth (London, UK)

- Incagnoli (Rome, Italy)

- A. Jardé (prior to WWII) (Paris, France)

- Josef (Okinawa and Tokyo, Japan)

- V. Kohlert & Söhne (1840–1948 Graslitz, Czechoslovakia, 1948–1970s Kohlert & Co. Winnenden, Germany)

- Kreul (incl. Mirafone) (Tübingen, Germany)

- J. R. LaFleur (1865–1938, bought by Boosey & Hawkes) (London, UK)

- Larilee Woodwind Corp. (US) (Elkhart, Indiana, US)

- A. Laubin[38] (incl. "A. Barré") (Peekskill, New York

- G. LeBlanc (France, US)[39]

- Linton (Elkhart, Indiana, US)[40]

- F. Lorée[41] (incl. Cabart) (Paris, France)

- Louis (prior to WWII) (London, UK)[42]

- Malerne (until 1974, bought by Marigaux) (La Couture-Boussey, France)

- Marigaux[43] (Mantes-la-Ville, France)

- Markardt (until 1976, bought by Mönnig) (Erlbach, Germany)

- Mollenhauer (before WWII; now only recorders) (Fulda, Germany)

- Gebr. Mönnig – Oscar Adler (Markneukirchen, Germany)[44]

- John Packer (Taunton, UK)[45]

- Patricola (Castelnuovo Scrivia, Italy)[46]

- Püchner (Nauheim, Germany)[47]

- Karl Radovanovic (Vienna, Austria)[48]

- Rigoutat (incl. RIEC) (Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, France)[49]

- A. Robert (prior to WWII) (Paris, France)

- Sand N. Dalton, instrument maker (Lopez Island, Washington)[50]

- Selmer (incl. Bundy, Lesher, Omega, Signet) (France, US)

- Tom Sparkes (Hornsby, New South Wales, Australia)[51]

- Ward & Winterbourne (London, UK)

- Guntram Wolf (Kronach, Germany)[52]

- Yamaha (Japan)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Fletcher & Rossing 1998, 401–403.

- ^ "Sound Characteristics of the Oboe". Vienna Symphonic Library. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "Why do orchestras tune to an 'A'?". Classic FM. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- ^ "The Amazing Instruments of the Orchestra".

- ^ "Difference Between a Clarinet and an Oboe". 22 July 2022.

- ^ J.B. (1695). The Spritely Companion. London: printed by J. Heptinstall for Henry Playford. p. 2. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ Kushner 1993, 167: "The oboe: official instrument of the International Order of Travel Agents. If the duck was a songbird it would sing like this. Nasal, desolate, the call of migratory things."

- ^ American Symphony Orchestra League. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. 2001. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.00790.

- ^ "ifCompare". ifCompare.de. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Julia. "Executive Director of the Rockford Symphony Orchestra". Rockford Symphony Orchestra. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "About the Orchestra" American League of Orchestras, (accessed January 1, 2009).

- ^ "Oboe vs. Bassoon: Similarities and Differences".

- ^ Joppig 1988, 208–209.

- ^ "Reed Styles and Reed Testing". Oboehelp. 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2020-01-10.

- ^ "How to Play the Oboe:The most attention is paid to the reeds - Musical Instrument Guide - Yamaha Corporation". Yamaha.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ legereadmin. "Oboe Reeds". Légère Reeds. Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- ^ Geoffrey Burgess and Bruce Haynes (January 2004). The Oboe. The Yale Musical Instrument series. p. 9. ISBN 0-300-09317-9.

- ^ Marcuse 1975, 371.

- ^ Burgess & Haynes 2004, 27.

- ^ Burgess & Haynes 2004, 28 ff.

- ^ Carse 1965, 120.

- ^ Burgess & Haynes 2004, 102.

- ^ Haynes & Burgess 2016.

- ^ Haynes & Burgess 2016, 176.

- ^ Burgess & Haynes 2004, 212.

- ^ "Modern Woodwind Instruments". Guntram Wolf. Archived from the original on August 3, 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Howe 2003.

- ^ Hurd, Peter. "Heckelphone / Bass Oboe Repertoire". oboes.us. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Howe & Hurd 2004.

- ^ "Zelenka". Jdzelenka.net.

- ^ Hinayana, John Palmer

- ^ Coltrane Discography Archived 2009-01-02 at the Wayback Machine Dave Wild

- ^ "Maria Schneider: Concert in the Garden Reviews/Credits". mariaschneider.com. Maria Schneider. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ Album Credits for Sufjan Stevens Allmusic.com

- ^ "Gabriel". Spin. September 1986. p. 53.

- ^ Rascón, Eduardo García (2017-09-01). "The music of Star Wars analyzed: Across the Stars (Love Theme from Episode II)". Medium. Retrieved 2020-01-13.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Liam (August 18, 2015). "The Godfather Film Music Analysis by Liam Fitzgerald". Press. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ "A. Laubin, Inc. – Oboes and English Horns". Alaubin.com.

- ^ "Leblanc Clarinets - Never Look Back". Archived from the original on 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ^ "Linton Woodwinds Bassoons and Oboes". Archived from the original on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ^ "Lorée – Paris". loree-paris.com. 22 April 2013.

- ^ "Nora Post Home". Norapost.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Home - Oboe Marigaux". Marigaux.com.

- ^ "Gebr. Mönnig". Archived from the original on 2002-05-12. Retrieved 2005-06-05.

- ^ "Musical Instruments UK For Sale | Woodwind & Brass | John Packer". Johnpacker.co.uk. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Patricola". Patricola.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Quality is the first word at Püchner | J.Püchner Spezial-Holzblasinstrumentebau GmbH". Puchner.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Wiener Instrumente". Wienerinstrumente.at. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Rigoutat". Archived from the original on 2006-02-17. Retrieved 2005-07-26.

- ^ "Sand N. Dalton Baroque and Classical Oboes". Baroqueoboes.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Tom Sparkes Oboes » Musical Instrument Repair, Service and Sales". Tomsparkesoboes.com.au. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Guntram Wolf". Archived from the original on 2009-06-16. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

References

[edit]- Burgess, Geoffrey; Haynes, Bruce (2004). The Oboe. The Yale Musical Instrument Series. New Haven, Connecticut and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09317-9.

- Carse, Adam (1965). Musical Wind Instruments: A History of the Wind Instruments Used in European Orchestras and Wind-Bands from the Later Middle Ages up to the Present Time. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80005-5.

- Fletcher, Neville H.; Rossing, Thomas D. (1998). The Physics of Musical Instruments (second ed.). New York, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-1-4419-3120-7.

- Haynes, Bruce; Burgess, Geoffrey (2016-05-01). The Pathetick Musician. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199373734.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-937373-4.

- Howe, Robert (2003). "The Boehm System Oboe and Its Role in the Development of the Modern Oboe". Galpin Society Journal (56): 27–60 +plates on 190–192.

- Howe, Robert; Hurd, Peter (2004). "The Heckelphone at 100". Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society (30): 98–165.

- Joppig, Gunther (1988). The Oboe and the Bassoon. Translated by Alfred Clayton. Portland: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-12-8.

- Kushner, Tony (1993). Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes (single-volume edition). New York: Theatre Communications Group. ISBN 1-55936-107-7.

- Marcuse, Sybil (1975). Musical Instruments: A Comprehensive Dictionary (Revised ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-00758-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Baines, Anthony: 1967, Woodwind Instruments and Their History, third edition, with a foreword by Sir Adrian Boult. London: Faber and Faber.

- Beckett, Morgan Hughes: 2008, "The Sensuous Oboe". Orange, California: Scuffin University Press. ISBN 0-456-00432-7.

- Gioielli, Mauro: 1999. "La 'calamaula' di Eutichiano". Utriculus 8, no. 4 (32) (October–December): 44–45.

- Harris-Warrick, Rebecca: 1990, "A Few Thoughts on Lully's Hautbois" Early Music 18, no. 1 (February, "The Baroque Stage II"): 97-98+101-102+105-106.

- Haynes, Bruce: 1985, Music for Oboe, 1650–1800: A Bibliography. Fallen Leaf Reference Books in Music, 8755-268X; no. 4. Berkeley, California: Fallen Leaf Press. ISBN 0-914913-03-4.

- Haynes, Bruce: 1988, "Lully and the Rise of the Oboe as Seen in Works of Art". Early Music 16, no. 3 (August): 324–38.

- Haynes, Bruce: 2001, The Eloquent Oboe: A History of the Hautboy 1640–1760. Oxford Early Music Series. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816646-X.

External links

[edit]- Peter Wuttke: The Haynes-Catalog bibliography of literature for oboe written between 1650 and 1800.

- A Guide to Choosing an Oboe Student, intermediate & professional oboes explained.

- Experiments in Jazz Oboe by Alison Wilson (archive link)

- Oboist Liang Wang: His Reeds Come First NPR story by Debbie Elliott

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Oboe sound gallery Archived 2018-03-03 at the Wayback Machine of clips of dozens of prominent oboists in the United States, Europe, and Australia

- Fingering chart from the Woodwind Fingering Guide

- Fingering chart for Android devices

- Pictures of oboe reeds made by famous oboists