Free French Air Forces

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (March 2019) |

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2011) |

| Free French Air Forces | |

|---|---|

| Forces Aériennes Françaises Libres | |

Free French Air Forces roundel | |

| Active | 17 June 1940–8 May 1945 |

| Country | |

| Type | Air force |

| Role | Aerial warfare |

| Size | 900 (1941) |

| Part of | |

| Engagements | World War II |

The Free French Air Forces (French: Forces Aériennes Françaises Libres, FAFL) were the air arm of the Free French Forces in the Second World War, created by Charles de Gaulle in 1940. The designation ceased to exist in 1943 when the Free French Forces merged with General Giraud's forces. The name was still in common use however, until the liberation of France in 1944, when they became the French Air Army. Martial Henri Valin commanded them from 1941 to 1944, then stayed on to command the Air Army.

French North Africa (1940–1943)

[edit]

On 17 June 1940, five days before the signing of the Franco-German Armistice, the first exodus of 10 airmen took flight from Bordeaux-Mérignac Airport to England. Others rallied to General Charles de Gaulle from France and French North Africa between June 1940 and November 1942. A contingent of volunteers from South American countries such as Uruguay, Argentina and Chile was also created, as Free French officials recruited there personally. From a strength of 500 in July 1940, the ranks of the FAFL grew to 900 by 1941, including 200 flyers[clarification needed]. A total of 276 of these flyers were stationed in England, and 604 were stationed in overseas theaters of operation. In the summer of 1940 General de Gaulle named then-Colonel Martial Henri Valin as commander-in-chief of the FAFL. Valin was at the French military mission in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil at the time of his appointment and he had to complete his assignment there by February 1941. It took him 45 days to get to London to see de Gaulle and it was not until 9 July that Valin formally took office, taking over from the caretaker commander, Admiral Emile Muselier.

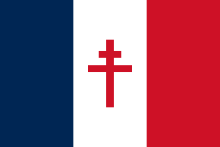

All FAFL aircraft were identified differently from those of the Vichy French air force, which continued to use the pre-war tricolor roundel. In order to distinguish their allegiance from that of Vichy France, the Cross of Lorraine - a cross with two parallel horizontal arms, with the lower arm slightly longer than the upper one - was the symbol of Free France chosen by Charles de Gaulle. The cross could be seen in the same places on FAFL aircraft where the roundels had been on all French military aircraft, that is, on the fuselage and upper and lower surfaces of the wings. The FAFL was formed with one “mixed” unit at RAF Odiham on August 29, 1940, under the command of Commandant (Major) Lionel de Marmier. One of its first jobs was to try to persuade the governors-general of colonies in French West Africa to not submit to the orders of the Vichy government, and instead join the Free French in their fight against the Axis Powers.

Operation Menace was an Allied plan to either persuade Dakar to join the Allied cause, or capture it by force. De Gaulle believed this was possible. Among the units taking part was the newly formed FAFL Groupe de Combat Mixte (GMC) 1, code-named "Jam", consisting of four squadrons composed of Bristol Blenheim bombers and Westland Lysander liaison/observation aircraft. The Battle of Dakar was a failure, however. The port remained in Vichy hands, the FAFL envoys were arrested and imprisoned at Dakar by the Vichy authorities, and de Gaulle's standing was damaged.

However, French forces in Cameroon and Chad in French Equatorial Africa, rallied to the Gaullist cause. Three detachments of French air force units based at Fort-Lamy (now N’Djamena in Chad), Douala in Cameroon, and Pointe-Noire in the Congo, operating a mixed bag of Potez and Bloch aircraft, which became part of the FAFL.

But Gabon remained loyal to Vichy, so, in mid- to late October 1940, FAFL squadrons set out on photo-reconnaissance and leaflet-dropping missions. The first combat between Vichy and the FAFL took place on 6 November 1940, when two Vichy air force aircraft took on two FAFL Lysanders near Libreville. Both aircraft sustained damage but made it back to base. Two days later, the first FAFL airmen were shot down and taken prisoner. Two days after that, Libreville was taken by Free French army troops, so the FAFL aircraft could now operate from the air base that had been used by their opponents a few days before. The French considered the fighting a “civil war” that Free France was winning, since now Libreville had joined the Gaullist cause. This would be the only time when opposing factions within FEA territory would fight each other openly.

Philippe de Hauteclocque, better known by his French resistance name of "Leclerc", later became one of the most famous French army generals in history, and had strong ambitions in North Africa. But he often revealed a complete lack of understanding of what the air force could actually do. When he wanted to bomb the Italian-held airfield at Koufra in Libya, he was told, matter-of-factly, that the squadrons could not carry out such a major mission, especially given their lack of experience in navigating over vast desert territory. Leclerc's reaction, based on his fury at the lack of air support during the German invasion of France, was ugly, and relations between him and the FAFL deteriorated rapidly.

A mission carried out by the recently formed Groupe de Bombardement (GRB) 1 (Lorraine), 1941, ended disastrously on February 4, 1942, when, out of four Blenheims sent to bomb Koufra, only a single one returned – and, even then, it was because of engine trouble. (One of the other three planes wasn't found until 1959.) On February 27, the Free French took Koufra airfield, and the enemy garrison surrendered two days later. Leclerc, for his part, still regarded aviation as a kind of appendage, of such minor importance that it might as well not be there to support the ground forces at all.

Following the Fall of France in 1940, there were French airmen who were determined to continue the fight against Nazi Germany. Some joined the RAF, whereas others joined the FAFL. Those who joined the RAF were fighting in the armed forces of a foreign nation, and technically breaking French civil law. They could have been considered mercenaries or filibusters, or charged with desertion in a court martial. On 15 April 1941, de Gaulle issued a formal declaration, requesting that French nationals in the RAF were to apply to be reincorporated in the FAFL by the 25th of April 1941. Any personnel making the transfer would be exempted from any wrongdoing.[2] Not all French personnel complied with this ruling. Some that had left Syria and Lebanon had specifically done so to join the RAF, and opposed de Gaulle. The RAF considered granting British citizenship to these men, so as not to alienate them. Whilst the FAFL certainly had a number of aircrew (several of whom had flown to the allies), it was weakened by its lack of ground crew, and a lack of spare parts for their French-built machines. While the aircrew of GRB 1 were all French, the ground crew were initially British airmen.[3] The arrival in the Middle East of the former Aéronavale ground crew from Tahiti in July 1941 was seen as a boost to the FAFL's maintenance personnel.[4]

The Groupe Bretagne was formed on 1 January 1942, with certain objectives in mind: U.S.-built Maryland aircraft would carry out long-range reconnaissance missions, the Lysanders close-support missions and the Potez liaison and transport missions. Yet it was not until March 3 that the first operational missions were carried out from Uigh el-Kébir, which had only been captured the previous day. The very next day, however, a Lysander crashed on landing, injuring its pilot, who had to be evacuated to hospital. On March 7, the FAFL had some success when some Lysanders successfully destroyed three enemy aircraft on the ground at Um el-Aranel; one of them was chased by an Italian fighter plane, but it managed to get back to base, albeit sustaining considerable damage.

For most of 1942, the Groupe Bretagne concentrated mostly on liaison and training flights, yet, in late autumn, Leclerc wanted to count on the FAFL to support ground offensives against the Italians in the wake of the victory of the British 8th Army against the Afrika Korps at the Second Battle of El Alamein and the Anglo-American invasion of Morocco during Operation Torch. However, lack of co-operation between Leclerc's general staff based at Algiers and the Allies seemed to indicate a power struggle between him and de Gaulle since the latter was in charge of the Free French forces in London. Though FAFL airplanes from the “Rennes” squadron of the Groupe Bretagne did engage Italian forces towards the end of 1942 and the beginning of 1943, problems with both weapons and the aircraft themselves (mostly engine trouble resulting in forced-landings) dogged the efforts of the aircrews. January 23, 1943, witnessed the fall of Tripoli – and the end of the air war for the Groupe.

The Anglo-American landing in North Africa in November 1942 was the starting point for the rebirth of the French Air Force, thanks to the commitment by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, of 1,000 planes, and the French began to receive U.S.-built aircraft to replenish its squadrons. GCII/5 was the first unit organized, at first consisting of a single squadron of P-40 Tomahawk fighters acquired from the United States Army Air Forces, because of its ties to the Lafayette Escadrille in World War I. Operating from a forward base at Thelepte, Tunisia, the two squadrons of GCII/5 fought alongside American units in clearing North Africa of Axis forces in 1943.

On July 1, 1943, the Algiers-based Armée de l'Air general staff (which received its orders from de Gaulle and General Giraud) and the FAFL general staff were merged and placed under the command of General Bouscat. He conducted the reorganization of the French Air Force, incorporating all elements coming from the ex-Vichy French Army in North Africa and the FAFL. Those forces included about twenty various Groups equipped mainly with Dewoitine D.520s, LeO 45s, Glenn Martin bombers, Bloch MB.175 reconnaissance aircraft, and an assortment of Amiots, Farmans, and Potez 540 transport aircraft.

One squadron, two identities: GC 2/7 (No.326 “Nice” Squadron) (1943–1945)

[edit]

Altogether, under the umbrella of the Allies (not just in North Africa, but also in Sicily and Corsica), there were nine FAFL fighter groups, three of which were designated as RAF fighter squadrons, namely No.326 (“Nice”), No.327 (“Corse”) and No.328 (“Provence”) Squadrons, with other units similarly named after regions in metropolitan France: Roussillon, Champagne, Navarre, Lafayette, Dauphiné and Ardennes. Similarly, there were six bomber groups (Bretagne, Maroc, Gascogne, Bourgogne, Sénégal and Franche-Comté), one reconnaissance group (Belfort) and one transport group (Anjou).

Following the dissolution of the Vichy French naval aviation arm, the second escadrille of the combat fighter group GC II/7 accepted several navy pilots into its ranks. In March 1943, it received its first British aircraft; Supermarine Spitfire Mk.Vb fighters. When GC II/7 was broken up in August, the squadron received two designations – one of which was French, the other British – by virtue of the fact that its complement included both French and British pilots. While the British designated the unit No.326 Squadron of the RAF, the French knew their squadron as GC 2/7, even though it was attached to No. 345 Wing of the Mediterranean Allied Coastal Air Force (MACAF). Its first mission as GC 2/7 was an armed reconnaissance mission on April 30, 1943, during the final phase of the war in North Africa, by which time the Luftwaffe had all but vanished, but ground-based Flak units still remained. By May 13, the Germans had surrendered in North Africa, and GC 2/7 had by then flown 42 missions, accumulating 296 sorties. On June 18, the squadron replaced its Mk.Vb Spitfires with the more capable Mk.IX variant, built originally to combat the German Focke-Wulf Fw 190, an example of which had been credited to GC 2/7 just seven days earlier.

September 1943 witnessed the participation of GC 2/7 in the liberation of Corsica, claiming seven enemy aircraft destroyed for the loss of two of its pilots. On the 27th, the squadron, alongside GC 1/3, had the distinction of becoming the first Armée de l'Air unit to be stationed on French soil, since the dissolution of the Vichy French air force the previous December, when it occupied the airfield at Ajaccio-Campo dell’Oro. Now part of No.332 Wing, the squadron's duties encompassed patrols over the island of Corsica itself, interception of German bombers attacking the island, protection of Allied convoys traversing the Mediterranean, attacks against German shipping berthed in Italian ports, and, from January 1944, the escort of USAAF bombers attacking targets in Italy. From the spring of 1944, GC 2/7 would involve itself both in strafing and dive-bombing attacks against ground targets in coastal regions of western Italy as well as the island of Elba, famous as the place of temporary exile of Napoleon in 1814 prior to his escape.

Finally, in September 1944, GC 2/7 found itself based in metropolitan France itself and was assigned to the same kind of missions that it had conducted over Italy. However, its commanding officer, Captain Georges Valentin, was shot down by flak over Dijon on the 8th, while another, Captain Gauthier, was shot down a week later, only he managed to reach Switzerland from where, having been interned, he “escaped” to rejoin his unit. As the front line advanced eastwards towards Reich territory, GC 2/7 went to Luxeuil, from where missions flown in early October resulted in four enemy aircraft being confirmed destroyed and another one counted as a “probable”. Christmas Eve saw GC 2/7 escorting B-26 bombers. "Around 20" enemy fighters attacked the formation, and GC 2/7 claimed four of them destroyed, but the French lost one of their pilots in the process.

GC 2/7 frequently clashed with the enemy as the Allies advanced farther into Nazi Germany – including a sighting of two Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighters on March 22, 1945, which were just too fast for the piston-engined Spitfires. On April 14, sixteen of the squadron's aircraft were escorting Lockheed F-5s when they were intercepted by a mixed formation of Bf 109s and Fw 190s, two of which were claimed by GC 2/7 pilots, yet one pilot was shot down and became – for the brief duration that the war in Europe yet had to run – a prisoner. By the time the war did end on May 8, GC 2/7 had, since its formation two years earlier, accomplished just over 7,900 sorties.

Red Star: the Régiment Normandie-Niemen fighting for the Soviet Union (1942–1945)

[edit]

Six months after the Germans invaded the USSR, talks aimed at closer co-operation between Free France and the Soviet Union resulted in a squadron being especially created, with an initial core of twelve fighter pilots being sent east. The Groupe de Chasse GC 3 Normandie was officially promulgated by de Gaulle on 1 September 1942, with Commandant Pouliquen in command. Mechanics, pilots and hardware were transported by rail and air via Tehran to Baku (now the capital of Azerbaijan). A period of training on the Yakovlev Yak-7 was completed by mid-February 1943 when Commandant Jean Tulasne took command of the groupe, which finally headed for the front on 22 March 1943.

The first campaign of GC 3, equipped with the Yakovlev Yak-1 fighter plane, lasted until 5 October, and encompassed the area of Russia between Polotniani-Zavod and Sloboda/Monostirtchina. From an initial aerial victory over an Fw 190 on 5 April the tally rose dramatically and the squadron became the focus of much Soviet propaganda, so much so that Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel (who was executed in 1946 after the Nuremberg trials) decreed that any French pilot captured would be executed.

Tragedy struck the squadron when the much-decorated Tulasne was reported missing in action after combat on 17 July requiring Commandant Pierre Pouyade to take command. In spite of the loss, GC 3 started to receive many Soviet unit citations and decorations as well as French ones. On October 11, de Gaulle accorded the groupe the title of Compagnon de la Libération. By the time GC 3 relocated to Toula on 6 November 1943, there were only six surviving pilots from the groupe, which had accumulated 72 aerial victories since joining the fighting.

1944 witnessed the expansion of the groupe to become a régiment, with a fourth escadrille joining its ranks. After training at Toula was completed on more advanced Yak-9D fighter planes, the new regiment rejoined the front line for its second campaign. This lasted until November 27 and took in the area between Doubrovka (in Russia) and Gross-Kalweitchen (in East Prussia, Germany). It was during this campaign that Joseph Stalin allowed the regiment to style itself Normandie-Niemen in recognition of its participation in the battles to liberate the river of that name. On October 16, the first day of a new offensive against East Prussia, the easternmost part of the Reich home territory, the regiment's pilots destroyed 29 enemy aircraft without loss. By the following month, the regiment was itself based in Reich territory. By the end of the year, Pouyade had been released from his command of the regiment and he, along with other veteran pilots, returned to France.

14 January 1945, saw the Normandie-Niemen regiment start its third campaign (from Dopenen to Heiligenbeil), concentrating in the East Prussian part of the German Reich, until victory in the east was formally announced on May 9, the day after VE Day in western Europe. By that day, the regiment had shot down 273 enemy aircraft and had received many citations and decorations. Stalin expressed his gratitude to the regiment by offering the unit's Yak-3s to France, to which the pilots returned to a hero's welcome in Paris on 20 June 1945.

Thus, the regiment became the only air combat group from a western European country (apart from the brief intervention by No. 151 Wing RAF when introducing Hawker Hurricanes to Russia) to participate in the war on the Eastern Front. Its flag bore the testimony of its battle experience with names such as Bryansk, Orel, Ielnia, Smolensk, Koenigsberg (later renamed Kaliningrad by the Soviets), and Pillau. It received the following decorations: from France, the Companion of the Légion d'Honneur, the Croix de la Libération, the Médaille militaire, the Croix de Guerre with six palmes; from the USSR, it received the Order of the Red Banner and the Order of Alexander Nevsky, with eleven citations between the two orders.

Axis Powers aircraft captured by Free French Forces

[edit]Aircraft of Free French Air Force

[edit]- Airspeed Oxford Mk.II trainer

- Amiot 143M bomber

- Avro Anson bomber/trainer

- Avro York VIP transport

- Beechcraft Model 18 liaison/trainer

- Bell P-39D Airacobra fighter

- Bell P-63A Kingcobra fighter

- Bloch MB.131 bomber

- Bloch MB.174 reconnaissance

- Bloch MB.175 bomber

- Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress - as transport

- Bristol Blenheim Mk.IV & Mk.V light bomber

- Caudron C.270 Luciole liaison

- Caudron C.400 Phalène liaison

- Caudron C.445 Goeland transport

- Caudron C.600 Aiglon liaison

- Caudron C.630 Simoun transport

- Caudron C.714 Cyclone fighter

- Cessna UC-78 Bobcat liaison

- Consolidated PBY Catalina patrol bomber

- Cunliffe-Owen OA.1 transport

- Curtiss Hawk 75 fighter

- Curtiss P-40E/F/N fighter

- de Havilland DH.80 Puss Moth liaison

- de Havilland DH.82 Tiger Moth trainer

- Dewoitine D.520 fighter

- Douglas A-24/SBD dive bomber

- Douglas DB-7 medium bomber

- Douglas Boston medium bomber

- Farman F.222 BN5 bomber

- Handley Page Halifax heavy bomber

- Hawker Hurricane Mk. IIC fighter

- Lioré et Olivier LeO 451 bomber

- Lockheed Model 12 Electra Junior transport

- Lockheed Hudson patrol bomber

- Lockheed F-5A/B Lightning photo reconnaissance

- Lockheed PV-1 Ventura patrol bomber

- Martin 167 bomber

- Martin 187 Baltimore bomber

- Martin B-26B/G Marauder medium bomber

- Morane-Saulnier M.S.230 trainer

- Morane-Saulnier M.S.315 trainer

- Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 fighter

- North American NAA-57 trainer

- North American B-25C/H Mitchell medium bomber

- North American F-6C Mustang photo reconnaissance

- Piper L-4 liaison

- Potez 25 observation

- Potez 29 transport

- Potez 540 transport

- Potez 63.11 reconnaissance

- Potez 650 transport

- Republic P-47D Thunderbolt fighter-bomber

- Supermarine Spitfire L.F.Mk.VB & VC fighter

- Supermarine Walrus rescue amphibian

- Universal L-7 liaison

- Stinson 105 Voyager liaison

- Vultee BT-13 Valiant trainer

- Vultee A-35 Vengeance dive bomber

- Vickers Wellington maritime patrol variant

- Westland Lysander Mk.III liaison

- Yakovlev Yak-1 & 1M fighter

- Yakovlev Yak-3 fighter

- Yakovlev Yak-7B fighter

- Yakovlev Yak-9 & 9T fighter

-

FAFL marked Spitfire (GC Ile de France/No. 341 Squadron RAF) in the Paris Le Bourget museum.

-

French Yak 3 from GC Normandie-Niemen.

-

French Dewoitine D.520.

-

French P-47D Thunderbolt (GC II/5 LaFayette).

-

GB II/20 Bretagne Martin B-26 Marauder.

-

Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 FAFL GC II/5 LaFayette.

Pilots of note

[edit]- Marcel Albert

- Pierre Clostermann The top-scoring Free French air ace in western Europe with 33 victories.

- Romain Gary

- Pierre Le Gloan Fighter pilot who flew with the Vichy French air force in North Africa.

- François de Labouchère

- Pierre Mendès France

- René Mouchotte

- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Reconnaissance pilot in North Africa after 1943.

- Bernard W. M. Scheidhauer, the only Frenchman to escape from Nazi prison camp Stalag Luft III; murdered by the Gestapo March 1944.

See also

[edit]- Free France

- Military history of France during World War II

- List of French paratrooper units

- Normandie-Niemen

- Free French Flight

- Free French Naval Air Service

- France during World War II

- Free French Forces

- French resistance

- List of military aircraft of France

- List of World War II Armée de l'Air aircraft

References

[edit]- ^ Free French Forces (1940-1944) at fivestarflags.com

- ^ AIR 23/1461 folio 14 accessed at The National Archives, Kew.

- ^ AIR 29/895 accessed at The National Archives, Kew.

- ^ AIR 8/371 accessed at The National Archives, Kew.

Sources

[edit]- Ehrengardt, Christian-Jacques (2000), La Croix de Lorraine sur le Tchad: les Lysander de la France Libre, in Aéro-Journal edition #13 (June–July 2000), Aéro-Editions SARL, Fleurance, pp. 4–16 (print edition in French)

- Ehrengardt, Christian-Jacques (2003), Le GC II/7 (2ème partie 1940–1945): GC 2/7 Nice (No.326 Squadron) , in Aéro-Journal edition #32 (August–September 2003), Aéro-Editions SARL, Fleurance, pp. 66–70 (print edition in French)

- Veillon, Jean (April 2003). "Les avions du Général: 17 Juin 1940" [The General's Aircraft: 17 June 1940]. Le Fana de l'Aviation (in French) (401): 53–59. ISSN 0757-4169.